A long-standing feature

Developers inspecting the user agent profile of a modern handset like the

Motorola XT682 ATRIX TV may be surprised to discover the following ImageCapable declaration which indicates whether a device can display images or not:

Yes

This clause is a remnant from a time when mobile phones boasted displays that

showed just a few lines of monospaced characters and could not render bitmap

images. As a remedial feature, mobile clients included a set of glyphs conveying

stereotypical representations of actions, states and objects. These graphical

symbols, frequently stored as a special font in the terminal, could be referred

to in Web pages and served as a substitute for richer, but unprocessable pictures.

(HDML, a markup

format for the mobile Web elaborated in the mid-1990s, offered a syntactic

construct to this effect).

Pictograms were soon considered to be useful as such, and made their way into

i-Mode, WAP and UNICODE specifications.

Pictograms differ from icon resources of native smartphone applications:

- They are not specific to a single program, but are standard symbols accessible

from all Web applications. The drawback is that their pre-defined style does not

allow for a brand or organization-specific look-and-feel. - They do not have to be explicitly installed, for they are built in the client

software. Relying upon pictograms potentially reduces network traffic, as the

corresponding images need not be downloaded to the terminal. - Because they are usually handled like characters, it is straightforward to embed

them in a normal text flow. On the other hand, they are often unsuitable as

components of a graphical user interface.

Whether in household appliances, packaging, or car dashboards, pictograms are ubiquitous in daily life; their application in mobile services is thus a natural step.

Application

Symbols with easily recognizable semantics can improve the usability of mobile Web

applications when used judiciously, for example in the following cases:

- Distinguishing similar elements from each other In the mobile Web, a clickable link may serve to navigate to another Web page;

to initiate a file download; to establish a telephone call or a video call; to

send an SMS, an MMS or an e-mail. A pictogram identifies the type of action

corresponding to each URL. - Drawing attention to specific items A pictogram makes elements with important properties stand out:

- marking items in a list which have been recently modified;

- tagging those form fields that contain erroneous values;

- signalling that the activation of a button or a link entails a side-effect.

- Summarizing information If a picture is worth a thousand words, a pictogram is possibly worth a

short sentence – as demonstrated by entrenched practices and conventions:- railway timetables rely upon symbols to condense instructions such as “seat

reservation is compulsory”, “runs only on Saturdays”, etc; - tourist guides summarize the description of an accommodation with symbols

for the hotel category and its amenities; - meteorological forecasts provide overviews constructed out of images for

each weather condition (e.g. “heavy snow shower during the day”).

- railway timetables rely upon symbols to condense instructions such as “seat

- Expressing concepts Pictograms act as signifiers so that textual expressions of those concepts

are never employed. Well-known instances are emoticons and traffic signs.

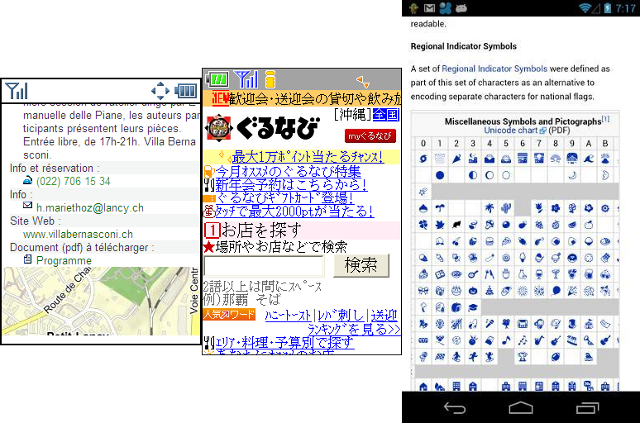

The preceding picture illustrates various forms of pictograms. From left

to right: a WAP XHTML document with symbols identifying link types; a typical

i-Mode page generously spiced with emojis; and a Wikipedia article showing

support for ISO pictographs on an Android handset.

Just like with many other aspects of the mobile Web, the deployment of this

venerable, albeit little-known building block must cater for various generations

of competing standards and discrepancies between implementations. In the following,

we survey the ways to declare pictograms in mobile Web pages and provide

correspondence tables between relevant symbol dictionaries.

Openwave icons

The browser developed by the firm Openwave (formerly called Unwired Planet, then

phone.com, today Myriad) is the longest serving mobile Web client in existence,

and is still deployed on numerous handsets with limited hardware capabilities.

It supports a form of pictograms identified by name or by number:

<img alt="" width="32" /> <img src="https://www.site.ch/star.gif" alt="*" width="32" />

The syntax works in XHTML and WML. Attribute localsrc takes

precedence over src and alt, in both cases displaying

the pre-defined icon star2.

The numbering scheme is recommended. Recognizing an Openwave browser is

easy, since its user agent identifier matches the egrep/Perl pattern:

(UP.Browser/[0-9.]+)|([Oo]pen[Ww]ave[/ ]?[0-9.]+)

| Version | Icon range | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 4.1 | 1 – 175 | The browser implements WML |

| ≥ 5.0 | 1 – 175, 500 – 518 | The browser also implements XHTML |

| ≥ 6.1 | 1 – 175, 500 – 536 | |

| ≥ 6.2 | 1 – 175, 500 – 561 | The browser supports WAP pictograms |

Nowadays, the original Openwave browser documentation can be retrieved only

from the Internet archive.

To this day, the Japanese operator KDDI commercializes phones featuring

Openwave software which, depending on the device class, incorporates built-in

icon sets supplementing the basic dictionary, or retrieves them as external

resources.

| Class | Icon range | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| A, B | 1 – 175 | 176 – 330, 500 – 518 as downloadable images; old models |

| C (1) | 1 – 304 | 305 – 330, 500 – 518 as downloadable images; old models |

| C (2) | 1 – 304, 500 – 518 | |

| D (1) | 1 – 334 | some models with animated icons |

| D (2) | 1 – 518, 700 – 822 | some models with animated icons |

| D (3), F | 1 – 518, 700 – 828 | some models with animated icons in D; no animations in F |

KDDI publishes on its WWW site a correspondence table between handset models

and supported icon ranges. Although all pictograms are assigned names, they

are usually embedded in Web pages with the Openwave numbering scheme.

Icons in overlapping ranges are compatible across all Openwave devices, but

slight variations exist: several arrows pointing straight upwards or downwards

(numbered 42, 43, 70, 71) become oblique in later implementations, whereas some

simple triangles become doubly tipped ones (7, 8, 34, 35).

WAP pictograms

The WAP standard from the Open Mobile Alliance comprises a dictionary of

62 core and 205 optional pictograms, markup to declare them, and a fall-back

mechanism in case a symbol is not implemented in the handset. In XHTML mobile

profile:

<object data="pict:///core/info/new" width="300" height="150"> <img src="http://mobile.site.ch/new.png" width="32" alt="NEW" /></object>

The browser outputs the pictogram for new if locally available;

otherwise, it downloads the file indicated in the img tag,

or displays the string in the alt

attribute if the image itself cannot be rendered. Older browsers (such as

Motorola MIB) may subject pictograms to the same restrictions as external

bitmaps – for instance enforcing a limit on the number of images that can

appear on a Web page.

The local presence of specific symbols may vary from a browser version to

another; the following compatibility table therefore considers whether the

client software recognizes the WAP pictogram syntax and defaults correctly

to an external image when appropriate.

| OS / Browser | Vendor | Version | Support | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Android | ≤ 4.1 | displays error placeholder | ||

| Bada / Dolfin | Samsung | ≥ 2.0 | uses the fall-back | |

| Blackberry | RIM | ≤ 7.1 | uses the fall-back | |

| iOS / Safari | Apple | ≤ 6.0 | error alert, empty placeholder | |

| Meego | Nokia | ≥ 8.5 | uses the fall-back | |

| MIB | Motorola | ≥ 2.2 | core set; emotion set ≥ 2.2.1 | |

| Mobile IE | Microsoft | ≤ 9.0 | uses the fall-back | |

| NetFront | Access | ≥ 3.2 | implements the core set | |

| Obigo | Teleca | ≥ Q05A | implements the core set | |

| Opera Mini | Opera | ≥ 4.0 | uses the fall-back | |

| Opera Mobile | Opera | ≥ 10.0 | uses the fall-back | |

| S40 | Nokia | ≤ 6th ed. | displays error placeholder | |

| SEMC | SonyEricsson | ≥ 4.0 | implements the core set | |

| Symbian | Nokia | < 7.0 | uses the fall-back | |

| ≥ 7.0 | displays empty placeholder | |||

| TSS | Samsung | ≥ 2.5 | uses the fall-back | |

| UP.Browser | Openwave | ≥ 6.2 | implements the core set |

It appears that, while most browsers recognize the syntax declaring WAP

pictograms, this feature is fully supported only by legacy browsers not

based on Webkit and explicitly preferring XHTML mobile profile over HTML

and XHTML basic. This presumably excludes the newest generation of the

NetFront (NX), Obigo (v. 10) and Myriad (Openwave v. 9) software built

upon Webkit, which could not be tested at the time of this writing. One

should also keep in mind that interactive mobile Web validators such as

mobileOK

and

mobiReady

are geared towards XHTML basic, and hence may erroneously flag WAP

pictograms as mobile-unfriendly resources.

The official reference for WAP pictograms is published on the

OMA

WWW site.

ISO pictograms

ISO normalized numerous pictograms with

UNICODE 6.0, refining proposals

originally submitted by Google and Apple to harmonize Japanese emojis.

The corresponding code points are reserved

in various blocks of the UNICODE space, chiefly “miscellaneous symbols and

pictographs”, “emoticons”, and “enclosed alphanumerics supplement”; blocks

“transport and maps”, “miscellaneous symbols and arrows”, “miscellaneous

symbols”, “dingbats”, “enclosed alphanumerics” also contain useful pictograms.

Web pages access all these symbols via numeric character references:

? <!-- code point U+1F31F represents a star -->

ISO pictographs are thus dealt with exactly like characters; there is no

graceful fall-back if the necessary font is not installed in the

terminal – missing glyphs might appear as question marks, black squares, or

blank spaces. Absent a Javascript routine to test the existence of specific

glyphs on a client, support for ISO pictograms must be determined on the

application server via a device description repository.

Since they are resources of the operating system, pictographs are in principle

not tied to the browser and are available to other software modules as well.

However, because of their intrinsic nature as characters, some caution is required:

- Several character blocks of interest are located in the UNICODE Supplementary

Multilingual Plane. Third-party applications do not always handle characters

outside the Basic Multilingual Plane properly. As a consequence, some symbols

may be correctly displayed, while others are unrecognised. This appears to be

the case with Opera Mobile, which does not render all standard ISO pictographs

enabled on Android 4.1. - Pictographs are usually provisioned through the default system typeface built

in the terminal. They may become inaccessible if the user switches his browser

or general user interface preferences to a different font. - Content styled with specific typefaces raises similar problems. Regrettably, CSS

offers no construct to force a textual element or a numeric character reference

to be rendered in the context of the default client font.

In the following, we consider the pictograms listed in tables of sections

7 and 8.

IPR symbols refer to signs for “copyright”, “trademark”

and “registered trademark”.

| OS | Version | core | emotions | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Android | ≥ 4.1 | Extensive coverage of the ISO norm, with just a couple of omissions in the core dictionary. | ||

| Bada | ≥ 2.0 | Supports circled digits, IPR symbols and a couple of isolated pictographs. | ||

| iOS | ≥ 6.0 | Exhaustive provision of “emoticons” and “miscellaneous symbols and pictographs”. | ||

| Meego | ≥ 1.2 | Circled digits, most arrows, IPR symbols and a handful of other pictographs. | ||

| Symbian | ≥ Belle | Implements circled digits 1 to 9, IPR symbols and the single traditional smiley. | ||

| Windows Phone | ≥ 7.5 | Good coverage, except for some blocks like “miscellaneous symbols and arrows”. |

With Bada, BlackberryOS, Meego, Symbian and WebOS being either wound down,

neglected or undergoing an uncertain overhaul, support for ISO pictographs

is likely to remain the preserve of Windows Phone, iOS and Android in the

foreseeable future. Only Nokia S40 might be in a position to adopt this

feature in the short term.

Emojis

Mobile applications developed in the Far East rely extensively on pictograms.

The Japanese mobile Web is a world unto itself, and its implementations of

pictograms (called emojis) exhibit a number of peculiarities:

- Each mobile network operator (Willcom, Softbank, NTT DoCoMo, KDDI) defines

its own set of emojis. While dictionaries overlap, there is no bijective

relation between them. - Just like with ISO pictographs, Japanese emojis correspond to symbols in

the code space of the document character set. However, because of legacy

character encodings, character references vary depending on whether Web

pages are formatted in a UNICODE-compliant encoding (such as UTF-8) or

not. For instance, the new symbol in i-Mode is represented by decimal

character reference廬in pages encoded with

Shift_JIS (corresponding to code point 0xF982 in the Shift_JIS space),

but by the hexadecimal referencein pages encoded

with UTF-8. - In some environments, a pictogram may be directly entered as a sequence of

bytes corresponding to its character encoding. - The set of emojis and their encoding may differ amongst user agents in the

same device (for instance the electronic mail client and the browser).

This article at mobiForge

clarifies the underlying concepts and the intricacies of character encoding.

| Operator | Dictionary | Emoji | Representation of symbol “telephone call” |

|---|---|---|---|

| DoCoMo | 2 levels 252 symbols max. |

沈 (Shift_JIS) (UNICODE) |

|

| KDDI | 7 levels 647 symbols max. |

(Shift_JIS) (UNICODE) |

|

| Softbank | 6 levels 485 symbols max. |

chr(27).'$E$'.chr(15) (PHP string equivalent of Shift_JIS binary code) (UNICODE) |

|

| Willcom | 2 sets 163 symbols + 252 i-Mode emojis |

(Shift_JIS, Willcom-specific)沈 (Shift_JIS, i-Mode compatible) |

Operators have published (mainly in Japanese) detailed documentation about

their versions of emojis; they can be obtained from the WWW sites listed above.

Comprehensive correspondence tables describing how to insert emojis into Web

pages are presented at trialgoods.com.

In 2012, Japanese operators harmonized the design of their pictograms in the

style of i-Mode emojis.

Emojis are so popular that Apple was compelled to implement a version derived

from the Softbank dictionary upon launching the iPhone in the Japanese market.

Version 5.0 of iOS also made these pictograms generally available to non-Japanese

iPhone models after a reorganisation to comply with the ISO norm – which implies

that pre- and post-iOS 5.0 devices refer to emojis through separate numeric ranges.

| iOS version | emojis | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 2.2.1 | 469 | pictograms stored in a private code space e.g. symbol glowing star: |

| ≥ 5.0 | 468 | most pictograms re-mapped to standard UNICODE ranges e.g. symbol glowing star: ? |

| ≥ 6.0 | 845 |

The site iemoji.com lists each

iOS emoji with its numeric encodings.

Core dictionary

While there is ample on-line documentation about finding equivalent

symbols in Japanese emoji dictionaries, such information is sorely

lacking for the formats used in the rest of the world. We present here

a correspondence table between WAP, Openwave, ISO, and iOS pictograms.

The entries are organized according to the core WAP dictionary, and

therefore deal with a limited subset of the standards under consideration.

This is justified on the following grounds:

- The entire set of potentially relevant symbols defined by ISO inside

various UNICODE character blocks amounts to well over 1300 items, and

would at any rate result in an unwieldy table. - Feature phones, most of them running a WAP or Openwave browser, currently

represent about 75% of the installed base of handsets worldwide. - The core dictionary covers the most commonly useful symbols, and, to our

knowledge, is the only one to have been fully ported to WAP terminals.

Hence, these tables should prove especially useful when setting up universally

accessible mobile Web sites – despite the fact that several pictograms

(especially “beginner”, “clear” and

“toll-free”) betray their Japanese

origins. Developers exclusively targeting modern smartphones need only

refer to the ISO norm when inserting pictograms in their applications.

| WAP | Openwave | ISO | WP | android | iOS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class – name | Nr | Name | Code | 7.5 | 4.1 | ≥ 5.0 | < 5.0 | |

| core/arrow | ||||||||

| up | 42 | uparrow2 | 2B06 | E232 | ||||

| down | 43 | downarrow2 | 2B07 | E233 | ||||

| right | 70 | rightarrow2 | 27A1 | E234 | ||||

| left | 71 | leftarrow2 | 2B05 | E235 | ||||

| upperRight | 537 | upperRight | 2B08 | 2197 | 2197 | E236 | ||

| upperLeft | 538 | upperLeft | 2B09 | 2196 | 2196 | E237 | ||

| lowerRight | 539 | lowerRight | 2B0A | 2198 | 2198 | E238 | ||

| lowerLeft | 540 | lowerLeft | 2B0B | 2199 | 2199 | E239 | ||

| fingerUp | 541 | fingerUp | 1F446 | E22E | ||||

| fingerDown | 542 | fingerDown | 1F447 | E22F | ||||

| fingerRight | 141 | righthand | 1F449 | E231 | ||||

| fingerLeft | 140 | lefthand | 1F448 | E230 | ||||

| core/button | ||||||||

| 1 | 527 | one | 22460 | 5 |

0031 20E3 | E21C | ||

| 2 | 528 | two | 22461 | 5 |

0032 20E3 | E21D | ||

| 3 | 529 | three | 22462 | 5 |

0033 20E3 | E21E | ||

| 4 | 530 | four | 22463 | 5 |

0034 20E3 | E21F | ||

| 5 | 531 | five | 22464 | 5 |

0035 20E3 | E220 | ||

| 6 | 532 | six | 22465 | 5 |

0036 20E3 | E221 | ||

| 7 | 533 | seven | 22466 | 5 |

0037 20E3 | E222 | ||

| 8 | 534 | eight | 22467 | 5 |

0038 20E3 | E223 | ||

| 9 | 535 | nine | 22468 | 5 |

0039 20E3 | E224 | ||

| 0 | 536 | zero | 224EA | 0030 20E3 | E225 | |||

| core/action | ||||||||

| makePhoneCall | 155 | phone2 | 1F4F2 | E104 | ||||

| find | 119 | magnifyglass | 1F50D | E114 | ||||

| userAuthentication | 517 | personal | 1F194 | E229 | ||||

| password | 543 | password | 1F511 | E03F | ||||

| nextItem | 544 | nextItem | 1F517 | 6 |

||||

| clear | 545 | clear | 1F191 | 6 |

||||

| stop | 98 | stopsign | 26D4 | 6 |

1E337 | |||

| top | 35 | uptri2 | 325B2 | 1F53C | E24C | |||

| next | 8 | righttri2 | 325C0 | E23A | ||||

| back | 511 | back | 325B6 | E23B | ||||

| 34 | downtri2 | 25BC | 1F53D | |||||

| core/message | ||||||||

| receive | 546 | receive | 1F4E8 | 6 |

||||

| send | 547 | send | 1F4E9 | E103 | ||||

| message | 108 | envelope1 | 1F4E7 | 6 |

||||

| document | 56 | document1 | 1F4C4 | 6 |

||||

| attachment | 143 | paperclip | 1F4CE | 6 |

||||

| folder | 79 | folder1 | 1F4C1 | 6 |

||||

| inbox | 154 | inbox | 1F4E5 | 6 |

1E101 | |||

| outbox | 153 | outbox | 1F4E4 | 6 |

1E102 | |||

| core/state | ||||||||

| secure | 138 | lockkey | 1F512 | E144 | ||||

| insecure | 548 | insecure | 1F513 | E145 | ||||

| copyright | 81 | copyright | 00A9 | 5 |

E24E | |||

| trademark | 54 | trademark | 2122 | 5 |

E537 | |||

| underConstruction | 549 | underConstruction | 1F6A7 | E137 | ||||

| beginner | 550 | beginner | 1F530 | E209 | ||||

| 82 | registered | 00AE | 5 |

E24F | ||||

| core/media | ||||||||

| book | 101 | book3 | 1F4D6 | E148 | ||||

| video | 115 | vidtape | 1F4FC | E129 | ||||

| cd | 551 | cd | 1F4BF | E126 | ||||

| dvd | 552 | dvd | 1F4C0 | E127 | ||||

| game | 45 | baseball | 1F3AE | 6 |

||||

| radio | 553 | radio | 1F4FB | E128 | ||||

| tv | 554 | tv | 1F4FA | E12A | ||||

| 171 | newspaper | 1F4F0 | 6 |

|||||

| core/info/td> | ||||||||

| notice | 555 | notice | 26A0 | E252 | ||||

| charged | 14 | dollarsign | 1F4B2 | 6 |

||||

| freeofcharge | 557 | freeofcharge | 1F193 | 6 |

||||

| new | 72 | gem | 1F195 | E212 | ||||

| position | 556 | position | 1F6A9 | |||||

| tollfree | 558 | tollfree | 27BF | E211 | ||||

| sharpdial | 559 | sharpdial | 0023 20E3 | E210 | ||||

| reserved | 560 | reserved | 41F4BA | E11F | ||||

| speechinfo | 561 | speechinfo | 1F50A | E141 | ||||

| 87 | creditcard | 1F4B3 | ||||||

Values are hexadecimal references to code points in the UNICODE space, and

images exemplary depictions of the associated symbols. Sometimes, an operating

system provisions the pictogram via a different UNICODE character, whose code

point is then mentioned explicitly. We suggest approximate substitutes whenever

a straightforward translation from one dictionary to another is infeasible:

- No direct match; entry is a proposed surrogate.

- iOS implements these pictograms through UNICODE combining character

sequences (numeral followed by an enclosing keycap) – a feature rarely

present elsewhere. Relying upon “circled digits” instead is more portable. - These symbols are more generic than ISO labelled arrows at code points

U+1F51D (“top”), U+1F51C (“soon”),

U+1F519 (“back”). - ISO character U+1F22F embodies exactly the meaning of “reserved”

(e.g. seat reservation), but is a Japanese ideogram. The proposed replacement

is more suitable for other countries. - Already available in Android version 1.6.

- Only available in iOS since version 6.0.

Emoticon dictionary

Class “emotions” is the sole subset of the optional WAP dictionary

that has enjoyed some (modest) level of support in mobile phones. It comprises a

number of smileys for which we propose equivalent iOS, ISO and Openwave

representations. This table also applies the tweaks and descriptive conventions

used for the core dictionary.

| WAP | Openwave | ISO | WP | android | iOS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class – name | Nr | Name | Code | 7.5 | 4.1 | ≥ 5.0 | < 5.0 | |

| emotions | ||||||||

| smile | 520 | 🙂 | 1F603 | E057 | ||||

| cry | 1F622 | E413 | ||||||

| sad | 521 | 🙁 | 1F614 | E403 | ||||

| angry | 1F620 | E059 | ||||||

| pullFace | 525 | 😛 | 1F61C | E105 | ||||

| inLove | 51 | heart | 1F60D | E106 | ||||

| shock | 1F631 | E107 | ||||||

| coldSweat | 1F613 | E108 | ||||||

| shakenHeart | 1F493 | E327 | ||||||

| brokenHeart | 1F494 | E023 | ||||||

| discourage | 524 | 😐 | 1F61E | E058 | ||||

| flash | 77 | lightbulb | 1F4A1 | E10F | ||||

| sleepy | 1F62A | E408 | ||||||

| anxious | 1F628 | E40B | ||||||

| surprised | 526 | 😮 | 1F632 | E410 | ||||

| tutting | 1F612 | E40E | ||||||

| happy | 523 | 😀 | 1F604 | E415 | ||||

| punch | 1F44A | E00D | ||||||

| wink | 522 | 😉 | 1F609 | E405 | ||||

| thumbsUp | 26 | 1plus | 1F44D | E00E | ||||

| thumbsDown | 27 | 1minus | 1F44E | E421 | ||||

| kiss | 1F618 | E418 | ||||||

| smell | 1F60F | E402 | ||||||

| cool | 1F60E | |||||||

| hug | 1F61A | E417 | ||||||

| trapped | 1F633 | E40D | ||||||

| shine | 1F60A | E056 | ||||||

| 68 | smileyface | 263A | E414 | |||||

Smileys have long been extremely popular in messaging applications and

Internet discussion forums. Every major platform (Yahoo! Messenger,

Microsoft Messenger, America Online, among others) offers a rich set

of icons to let users liven up the texts they send to each other.

Emoticons are entered as pre-defined identifiers or character sequences

(for instance :-) or 8-|).

The messaging clients of some mobile operating

systems (notably Windows Phone) follow a similar approach.

Service platforms

Unfortunately, major device description repositories provide very few

data describing pictographic terminal capabilities. Developers may resort

to attributes such as the type of browser or the version of the operating

system run by the handset in order to fine-tune the representation of mobile

pages.

Programs that map pictogram dictionaries and encodings to each other

are necessary when generating content for terminals implementing

different pictographic formats, or when exchanging messages amongst

them. Here is a sample of public-domain tools that translate between

popular Japanese conventions.

We are not aware of any similar gateway utilities for ISO, Openwave and WAP.Concluding remarksThe interest in pictograms was rekindled when Apple released an iPhone

model with an abundant collection of colourful icons embeddable in

applications and Web pages. The revision of UNICODE published in October

2010 increases the relevance of pictograms for smartphones, but feature

phones and legacy handsets have long been endowed with a comparable

capability – albeit via different mechanisms. The information presented

in this article should enable developers to decide how to integrate

pictograms in their Web sites – taking into account requirements about

application look-and-feel, the range of targeted devices, and the facilities

to configure their Web service platform with pictogram generators.We recommend a utilization of pictograms more parsimonious than what one

can often observe in Asian mobile Web sites. Hence, the core dictionary

should suffice for the first couple of – very common – scenarios listed

in section 2.Beyond this basic set, ISO specifies a profusion of idiosyncratic signs

for the Chinese horoscope, Japanese places and holidays, Nippon cuisine,

service ideograms, manga characters, as well as more universally interesting

pictographs related to office supplies, commercial and professional activities,

sports, games, vehicles, plants, animals, the weather, geometric shapes and

additional emoticons. WAP defines many optional items that map easily to

those ISO code points, but lacking support in WAP handsets makes this

compatibility immaterial in practice. On the other hand, about 160 actual

Openwave icons correspond to symbols scattered throughout UNICODE and may

prove occasionally useful when catering for low-end devices. Developers

can peruse the Openwave documentation to ascertain the equivalence of

individual pictograms on a case-by-case basis. Sites such as

shapecatcher.com and

fileformat.info

have query tools that facilitate the exploration of the UNICODE character space.Of course, the situation may arise where the symbol of interest is completely

unsupported by a handset or a standard. The manipulation of custom icons

(such as those used in the present article, extracted from the

fatcow collection of free icons)

is an issue to be addressed in another instalment.

| Language | DoCoMo | KDDI | Softbank | Willcom | iOS < 5.0 | ISO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUBY | ||||||

| Only UNICODE encoding. DoCoMo codes erroneously assumed identical to those of KDDI. | ||||||

| PHP | ||||||

| Only UNICODE encoding. Although not explicitly supported, iOS pre-5.0 uses Softbank codes. | ||||||

| PERL | ||||||

| Shift_JIS and UTF-8 encodings. Although not explicitly supported, iOS pre-5.0 uses Softbank codes. | ||||||

Leave a Reply