![]()

A lot has changed in a short time in Google’s beacon platform. Perhaps not to be unexpected given that it’s a relatively new technology. Beacons that you can purchase today generally have several broadcast modes to choose from, including iBeacon, Eddystone-EID, and Eddystone-URL. Some can broadcast multiple modes at once, while others must be configured in one mode, and will stay there until reconfigured.

Starting with Google’s Beacon platform can be daunting. While the Physical Web is simple on one level, once you dig deeper, things can get confusing quickly. It’s easy to get bogged down in overlapping APIs and services, without knowing which ones you might need. When Google first announced Eddystone Physical Web, things were very simple: press a button on a beacon, load up the configuration app on your phone, set the beacon URL via the app, and that’s it, the beacon broadcasts the URL until it dies.

Now beacon technology is baked into Android. In the beginning, you had to install the Physical Web App, or some third-party app, before you could receive beacon notifications. Now beacons can be detected by a device without having to install any third-party apps at all, thus lowering the barrier to usage.

However, a large number of related APIs, and multiple overlapping ways of getting up and running with the physical web, have led to a rather confusing landscape, and so in this article we try to make sense of this landscape.

Why is the beacon landscape confusing?

Some of the reasons are given below:

- Originally, the official Physical Web App from Google could be used to program beacons. A subsequent release removed this feature, leaving users with beacons that had been configured with this app unable to reconfigure them

- A web-based alternative that relies on Web-Bluetooth is recommended as the new way to configure beacons, despite Web Bluetooth being an experimental technology

- Another beacon app from Google, Beacon Tools, is available in the Play store, but this does not have the ability to configure beacons (it has a very different purpose as we’ll see later)

- The naming of the Physical Web project, a sub-project within Google’s Beacon Platform, appears to only refer to a certain type of beacon (Eddystone-URL beacons), despite other types of beacons delivering a very similar experience to the end user via other components of the Beacon platform

- There are quite a few location based services and APIs working in tandem that make up the beacon platform, and it can be a little overwhelming at first

- Due to an Android bug, all notifications for all users were disabled for two months at the end of 2016 until a fix could be rolled out, leaving developers confused about why notifications were not appearing.

Let’s start by looking at Google’s beacon platform, Google Beacons, as a whole.

Google Beacons

This is the umbrella project for Google’s Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Beacon platform. From its project page you can get an idea of what’s involved. Three main sections are listed prominently: Beacons in your app, Beacons without an app, and The Physical Web.

It’s worth noting that this page somewhat confusingly lumps the Beacon Dashboard and Proximity Beacon API under the Beacons in your app section, with the Android and iOS Nearby Messaging API. Placed next to the Beacons without an app section suggests that these components are only for use with native apps. In fact, the Beacon dashboard, as we’ll see later, can be used to manage beacons independently of whether they are used with apps or web. And the Proximity Beacon API is a REST API, making it platform agnostic.

Let’s take a look at some of the technologies of the Beacon platform. Where you go next will depend on what you want to achieve with your beacons, but from the point of view of this article, we’re interested mainly in beacons as an extension of, or as a discovery tool for, the web. So we won’t go into any aspect of the beacon platform that is exclusively for apps.

Undoubtedly, the simplest way to get started with beacons is via Google’s Physical Web and Eddystone beacons.

The Physical Web

The Physical Web, as described on its github project page, is an open approach to enable quick and seamless interactions with physical objects and locations.

At first take, the Physical Web seems to only refer to Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons that are configured to simply broadcast URLs. A device detects the beacon, a notification is shown on the device, and if the user taps the notification, the URL is opened in the browser. That’s it! It really is as straightforward as this.

Google designed the Eddystone-URL format to specify how beacons should broadcast URLs, so let’s take a look at this next.

Image source: The Physical Web

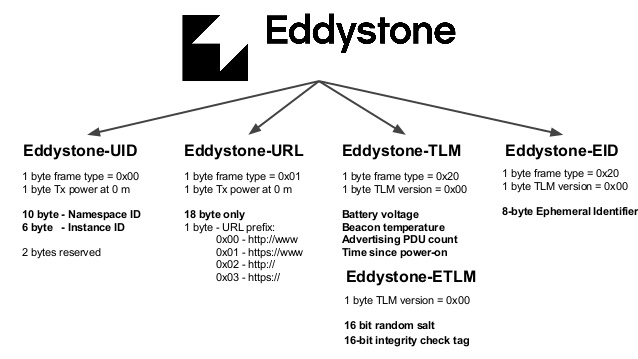

Eddystone Beacons

Eddystone-URL is the specification used for Physical Web beacons and it allows you to associate a URL with a beacon. To get started you use the beacon manufacturer’s app, or a compatible third-party app, to set the desired URL of your beacon. Then you physically deploy the beacon in the world, and you’re done. You can now sit back and wait as people receive notifications about your beacon and visit your website. Welcome to the Physical Web!

This simple idea unlocks a surprising wealth of applications, from targeted marketing to smart vending machines and parking meters.

We’ve talked about Eddystone-URL and the Physical Web previously, and noted interesting platform-specific quirks in terms of the display of notifications, so we won’t go into too much detail on different platform implementations here.

On the device side, how is the notification displayed? In the first version of the Physical Web, the beacons could only be detected and notifications displayed if the device had a beacon-detecting app installed, such as The Physcial Web app, or some other third-party app.

The next iteration of the Physical Web brought notifications to Chrome browser. Most Android devices, and many iOS devices have Chrome installed, so this development represented a significant increase to the reach of the Physical Web. Technically though, Chrome browser is an app, and so it wouldn’t be strictly true to say that the Physical Web didn’t need an app to function. In any case, this was a step in the right direction to complete app independence.

More recently still, support for the Physical Web was added to Google’s Nearby Notifications on Android. The Nearby Notifications API is baked into Android (4.4 and higher), so now the Physical Web was truly independent of apps on Android (although it still required Chrome to function on iOS).

So this is the basis of the Physical Web. It’s a self-contained project, based on Eddystone-URL, and relying on no dependencies (apart from Chrome on iOS).

Let’s see how to set up an Eddystone-URL beacon for the Physical Web.

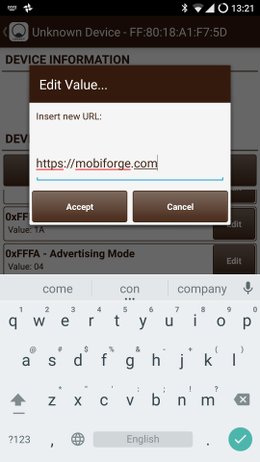

Configuring an Eddystone-URL beacon for the Physical Web

Configuring an Eddystone-URL beacon is pretty easy:

-

First put the beacon into configuration mode. This depends on the beacon model. For some beacons you need to press a button. Other beacons enter configuration mode for a defined amount of time after power up. Check your manual for your beacon.

-

Load up a beacon configuration app. Some manufacturers build their own configuration app, while other simply direct you to a Eddystone-compatible third party app such as the Eddystone app.

-

Find your beacon in the list of detected beacons, and select it. If it’s still in configuration mode you will be brought to a configuration screen. If not, go back to step 1!

-

Update the Eddystone-URL. Many beacons offer multiple broadcast modes, such as iBeacon, Eddystone-EID, as well as Eddystone-URL. Find the correct field and set your URL. Note that only HTTPS URLs will work here. In our case, we’ll use https://mobiforge.com. (Note that it’s sometimes recommended to use a link shortener here)

Configuring beacons with Accent Systems’ iBKS app (legacy) -

Make sure your beacon is configured to broadcast in Eddystone-URL mode. If your beacon can broadcast in multiple modes, check that it set to broadcast in the correct mode

-

Save and exit

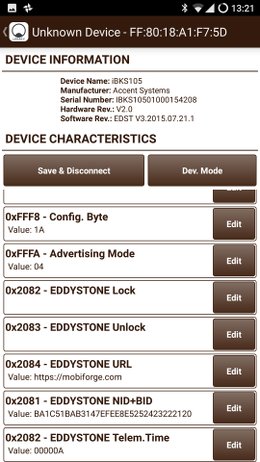

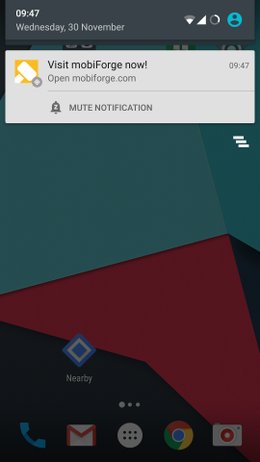

You should be ready to go! If you check your notifications you should at some point see a notification that looks something like this:

![]()

Physical Web notification display (left) and in Nearby interface (right)

There are a few things to notice about this notification:

- The Physical Web notifications are low-priorty, which means that they will appear in the notifications area, but they will not otherwise interrupt you, or be surfaced to your lock-screen

- The notification will use the title text from the URL as the notification text

- When viewing the notification in Nearby (you can find Nearby on your Android device in Settings > Google > Nearby), it displays the Physical Web logo

to the right of the notification, indicating it is a Physical Web/Eddystone-URL beacon

Using a link shortener

It’s recommended to use a link shortener for your Eddystone-URLs for two reasons:

- The Eddystone-URL protocol allows only 17 bytes per URL, so URL shorteners allow you to circumvent this restriction

- If you use a URL shortener that allows you to change the target URL, you will be able to update the target URL of the beacon without having to physically visit the beacon and reconfigure it

Other Eddystone formats: Eddystone-UID, Eddystone-EID, Eddystone-TLM

There’s more to Eddystone than we’ve mentioned so far. Eddystone-UID is a format where the beacon broadcasts an ID instead of a URL, and an app or service must decode or interpret the beacon signal.

Eddystone-EID (ephemeral ID) is a more recent security addition to the Eddystone format. It prevents beacons from being spoofed, and offers privacy and access control to beacons. If a bluetooth beacon constantly broadcasts the same ID, it can be hijacked. So instead, with Eddystone-EID, beacons can broadcast different rotating IDs over time.

Eddystone-TLM is a format for broadcasting telementry data such as battery level, temperature, and broadcast stats, at regular intervals.

With both Eddystone-UID and Eddystone-EID, beacons no longer broadcast a simple URL, so getting from beacon ID to URL becomes more difficult. A mechanism is needed to translate between what the beacon is broadcasting, and the desired target content. This could be an app, or a web service. Eddystone-EID in particular requires Google services for key exchange to access the beacon data. For Eddystone-UID, Google services is optional, but it’s either that or some other application.

Image source: Secon 2016

With Eddystone-URL, it’s more or less independent of anything else, set your URL and deploy your beacon. With Eddystone-UID and Eddystone-EID you’ll need to set up a Google Cloud Project, register your beacons with Google’s cloud platform, as well as configuring the actual beacons themselves. It’s definitely more work.

So, if you want to use Eddystone-UID beacons with the Physical Web, then things quickly get more complicated for your beacon project. Let’s see what it takes to get an Eddystone-UID beacon set up on on the Physical Web.

And note now that this is where Google’s definition of the Physical Web, as outlined on the Physcial Web project page, gets a little bit confusing. Eddystone-UID beacons are not specifically mentioned in the Physical Web documentation, but in terms of marking up real world object with beacons, and in terms of what the end user sees, it’s pretty similar; it just uses a different, but overlapping, infrastructure to deliver it.

But before we can get to this, we need to familiarise ourselves with some of the other technologies in Google’s Beacon platform.

What is Google Nearby?

Google Nearby is the scanning component of the Google beacon platform. It’s part of Google Play services and should be available on KitKat devices (Android 4.4) and higher. It has an interface that you can access on your device at Settings > Google > Nearby. Technically it’s comprised of several location-based (Nearby) APIs:

-

Nearby Messages: a publish-subscribe API that can pass small binary payloads between internet-connected Android and iOS devices. The devices needn’t be on the same network, but they need Internet connectivity.

Nearby uses a combination of Bluetooth, Bluetooth Low Energy, Wi-Fi and near-ultrasonic audio to communicate a unique-in-time pairing code between devices.

-

Nearby Connections: enables your app to easily discover other devices on a local network, connect, and exchange messages in real-time.

This API lets you build apps that can join multiple nearby Android devices together on the same local network. One device advertises on the network as the host, while other devices act as clients and send connection requests to the host.

-

Nearby Notifications: enables contextual discovery. This service allows you to associate a website or app with beacons, that can trigger low-priority notifications when scanned by devices that are nearby.

So, of these APIs, we are only really interested in the last one, Nearby Notifications, in our exploration of the Physical Web and beacon capabilities. It’s the mechanism by which the Physical Web became app-independent on Android. We’ll come back to Nearby Notifications later and we’ll walk through setting up web URL Nearby Notifications for BLE beacons.

The Google Beacon Dashboard

Another component of Google’s Beacon platform is the Beacon Dashboard. It’s a web based interface tied to a Google account, from which you can view and manage information associated with your Eddystone-UID/EID beacons. You can attach specific pieces of data with each beacon, such as placeIds corresponding to real world locations from the Google Places API, and notifications to be triggered when the beacon is encountered. Notifications can be URL links or app intents.

![]()

In addition, you can attach arbitrary blobs of data, called beacon attachments, with each beacon. Beacon attachments are essentially key-value pairs, and they can be retrieved either by the Nearby Messages API, a native API for iOS and Android apps, or via the Proximity Beacon API which is a REST API, so it can be used pretty much on any platform, including the web.

What is the Proximity Beacon API?

The Proximity Beacon API is a web service that allows you to manage your BLE beacons and associated data using a REST API. It’s a bit like a REST implementation of the Beacon Dashboard. Requests to the API are authorised via OAuth or with an API key.

An interesting aspect of this API is that it allows you to monitor the status of your beacons remotely. Beacons that implement Eddystone-TLM send telemetry data at regular intervals. Apps using the Nearby API automatically send telemetry data to Google’s beacon platform, and you can tap into this with the Proximity Beacon API. Telemetry data includes battery level, uptime, and beacon temperature. The beacon platform analyses the telemetry data, and can predict when the battery will die, as well as detecting if a beacon has been physically moved.

A typical request to list nearby beacons would be like this:

GET https://proximitybeacon.googleapis.com/v1beta1/beaconsWith a response similar to the following:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-length: 1799

Content-location: https://proximitybeacon.googleapis.com/v1beta1/beacons?q=status:active

Transfer-encoding: chunked

Vary: Origin, X-Origin, Referer

Content-type: application/json; charset=UTF-8

{

"beacons": [

{

"status": "ACTIVE",

"description": "Dot Beacon, reporting for duty!",

"indoorLevel": {

"name": "1"

},

"latLng": {

"latitude": 47.669377099999998,

"longitude": -122.1966037

},

"placeId": "ChIJTxax6NoSkFQRWPvFXI1LypQ",

"advertisedId": {

"type": "EDDYSTONE",

"id": "hZ3uYXQBwm2IsAAAAAAAyA=="

},

"beaconName": "beacons/0123abcd4567efgh890",

"expectedStability": "STABLE",

"properties": {

"type": "Radius Dot beacon",

"location": "Entryway"

}

}

],

"nextPageToken": "Civ55cv//f/9zN7NnMrGzZ7LnJ6bysbJnsmZzJ3Oz8/Pz8/Pz8/Pz8/PzP/+EAMh5L1umSgzmnQxBQHmb3DvF+sxZZVNTdNeID05AgACADQaAABQAFoLCdMiAswr49SsEAE",

"totalCount": "3"

}

The full Proximity Beacon API reference can be found here: https://developers.google.com/beacons/proximity/reference/rest/.

We’re not going to use this API in this article, but we’ll note that it could be used in your web project if you wanted, and leave it at that.

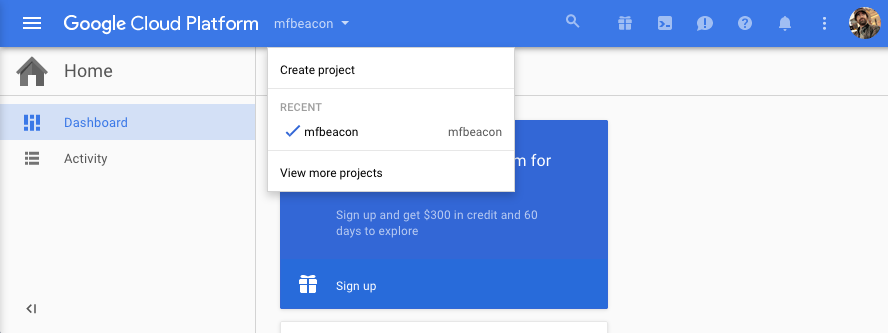

What is Google Console Cloud app management?

Another component you may have come across in the Beacon platform documentation is the Google Cloud App Management Console. We’ll mention it here only in passing because to get set up with Google’s Beacon Dashboard and Nearby, you need to set up a Google Cloud project, and you do this via the Google Console Cloud App management interface.

We’ll see how to do this later.

Nearby and the Physical Web

Nearby is sort of like DNS for Physical Web beacons. It allows you to decouple beacon identifiers from beacon data, and by doing so leverages the power of the cloud so that useful features such as remote beacon management and monitoring can take place. Your device sights a beacon, fetches its UID, and Nearby will translate that UID into a URL (among other things).

An immediate advantage of this setup is that you can manage your beacons from a centralised location, and you don’t physically need to be near the beacon to update its functionality. Instead you can log onto Google developers console, and manage things from there.

In the following sections, we’ll take a look at what’s involved in getting your beacons set up and registered in Google Nearby, and we’ll see how they can deliver notifications to BLE devices. The first thing to do is configure the beacons.

Configuring your BLE beacons

Depending on the type of beacon you have, it may be configured in different ways.

Physical Web App vs Beacon Tool app vs Physical Web web app

When the first versions of Physical Web beacons were released, an app—The Physical Web app—could be used to set up your BLE beacons. Later versions of this app then removed the URL configuration feature, and moved this instead to a Web-bluetooth enabled Web app (https://cf.physical-web.org)

In the meantime, another app, called Beacon Tool is used for configuring beacons to work with Google web services.

So, to be clear, if you’re setting up an Eddystone-URL beacon, you don’t need the Beacon Tools app, but you will need either manufacturers app, or a generic Eddystone-URL compatible app, to set up your beacons. If you’re lucky, the Physical Web web app might work for you, but we had no luck with it on various devices and beacon models.

If you are setting up an Eddystone-EID, Eddystone-UID beacon (or an iBeacon) then you will need the Beacon Tool app to register your beacon with the platform.

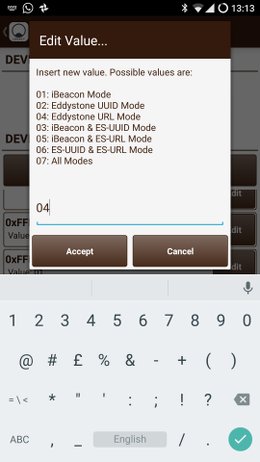

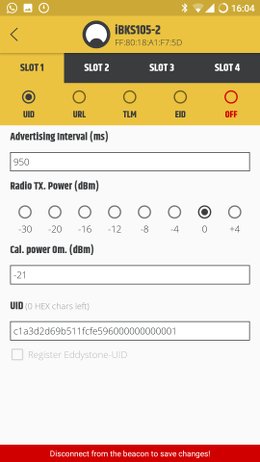

Configuring a beacon in Eddystone-UID mode

While Eddystone-URL beacons will appear in Nearby notifications automatically, beacons in other formats, such as Eddystone-UID, Eddystone-EID or iBeacon need to be registered on Google’s platform before they will appear in Nearby notifications. This is because since these other formats are not broadcasting a raw URL, they need an intermediary, whether an app or web service, to interpret the beacon data.

Choosing a unique UID for your beacons

Beacons are identified on the platform via their ID, and each ID can only be registered once on the platform. If you don’t change the ID of your beacon from its factory setting, there is a risk that somebody else can register a beacon with the same preset ID. Therefore, it’s important to set the ID of your beacon to something that makes sense for your company.

Eddystone-UID IDs are made up of a 10 byte namespace, and a 6 byte instance, making up 16 bytes or (32 hex characters). The namespace is supposed to be unique to a company or beacon project implementor, and the instance id should be unique within a company.

Google has two recommendations on how to construct your Eddystone-UIDs:

-

Truncated hash of your fully qualified domain name: create a SHA-1 hash of your domain name, and then take the first 10 bytes (20 characters) of the hash. This is your namespace. Then choose whatever 6 byte (12 characters) you like for the instance id that is unique across all your beacons.

-

Use a UUID tool to generate a 16 byte UUID. Then remove 6 bytes, from byte 5 to byte 10, and this gives you your namespace. Then choose whatever 6 byte (12 characters) you like for the instance id that is unique across all your beacons.

Configure your beacon in Eddystone-UID mode

Once you have your UID, you can follow more or less the same procedure as for Eddystone-URL beacons mentioned above. Instead of using a URL at step 4, find the correct field and input your UID instead.

In our case, we use method 2 above to generate our UUID: c1a3d2d6-fd66-4e8e-a163-9b511fcfe596. So our namespace is: c1a3d2d69b511fcfe596, and we’ll use 000000000001 as our instance part.

So the full UID is c1a3d2d69b511fcfe596000000000001.

Configuring beacons with Accent Systems’ iBKS app

Setting up a Google Cloud App project for your beacons

The next step is to set up a Google Cloud project for our beacon application. First, load up the Google Console Cloud App management interface.

Next, create a new project for yourself. For the examples in this article, we set up a project called mfbeacon. Make note of the project name you choose, you’ll need it later when you register your beacons with the platform.

When your project is finished setting up, you can load up the Beacon dashboard.

Associate your cloud project with the Beacon dashboard

If this is your first visit to the dashboard there won’t be too much to see just yet. You’ll need to select the project you just created to associate it with the Beacon platform. When you do this, it should tell you that you have no beacons registered, and prompt you to download the Beacon Tools app which you can download from the Play Store here.

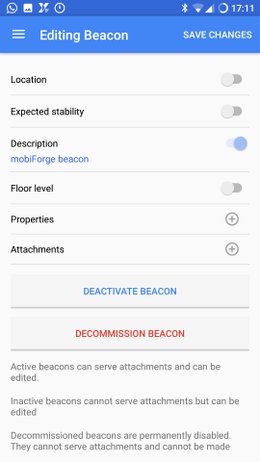

Registering a beacon with the Beacon Tools app

Now that you have configured your beacon, and you have set up your beacon project, you can now register your beacon with your project via the Beacon Tools app. After opening up the app on your bluetooth enabled device, you’ll need to

- Make sure you have selected your Google Cloud project that you created earlier

- Then select the beacon you just configured from the list of unregistered beacons:

You can set some of the associated data now if you want, such as giving your beacon a user-friendly name (if you don’t change the name, the Beacon dashboard will use the UID as the display name)

- Tap “Register Beacon”, and that’s it, you should now be able to see your beacon in the dashboard.

![]()

Setting up a beacon notification via the Beacon Dashboard

After registering your beacon with the Beacon Tool app, you can configure it via the dashboard, without ever having to physically visit the beacon itself. This is especially useful if you have a large number of beacons, or if they are deployed in remote locations.

In the beacon dashboard, select the beacon you just registered. You should now see the details for this beacon. From here you can associate a physical location with your beacon, and importantly, you can set up Nearby Notifications.

![]()

Click the drop-down beside View details, and select the Nearby notifications option.

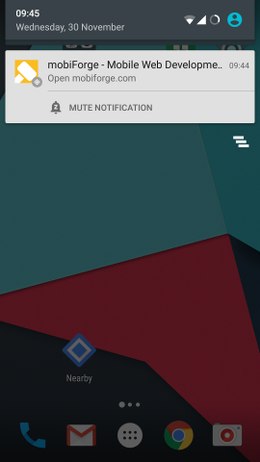

You can now set up a notification for a Web URL, or an App Intent. Choose Web URL, add the URL and some text to appear in the notification, click Save, and you’re done.

![]()

This is another advantage the Nearby approach has over the Eddystone-URL approach: notification text is configurable for the Nearby approach.

If everything has gone to plan, you should soon be able to see the notification on your Android device, when you swipe down from the top of the screen. Note that these are set up as low priority notifications. This means that they won’t pop up on the screen, but they will appear in the notification area when the user accesses it. Our new notification, with our configurable notification text, looks something like the image below.

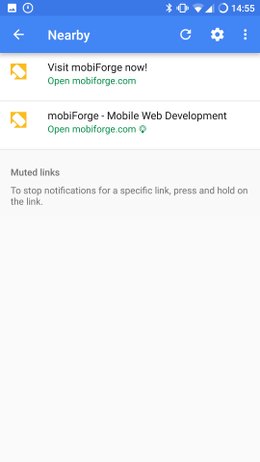

When we look at the Eddystone-URL/Physical Web and the Eddystone-UID/Nearby notifications together in the Nearby app, we can see the differences:

Developing for beacons

Developing and testing can sometimes be difficult. Part of the problem is because this is a young technology, the rules for notification display change from time to time. The most extreme example of this happened around September 2016, when all Nearby notifications were muted globally on Android for two months until mid November. Yes, muted for everybody, for all beacons! Due to an Android bug where notifications were persisting indefinitely, the platform muted all notifications until a new version of Google Play Services could be rolled out.

A common complaint by developers is that sometimes notifications that used to show up, no longer do. This is because there is an exponential backoff policy for notification display. When a notification is dismissed, Nearby Notifications will stop showing all notifications for a set period of time. This time period increases with each subsequent dismissal, until notifications are eventually completely disabled. The backoff policy will be reset when the user clicks on a notification or by viewing Nearby items in Settings > Google > Nearby.

A useful feature of Nearby on Android devices, is the ability to clear data. This should unmute muted notifications allowing you to view the notification experience as a first time visitor to your beacon.

The iOS elephant in the room

Perhaps one of the biggest drawbacks for the Physical Web right now is the patchy iOS support. While it is possible for Eddystone beacons to trigger notifications on iOS, there are yet several hurdles that will prevent widespread adoption:

-

Requires an app: one of the selling points of the Physical Web is that it just works, with no app install required. This is not quite true on iOS. The Physical Web on iOS relies on Chrome browser being installed on the user’s device. There are vast numbers of users of iOS who are happy with the default browser, or who may not really know what a browser is and that they have a choice

-

Requires Chrome notifications to be enabled in home widget: Physical Web notifications on iOS are delivered in the homescreen today widget. Before a user can receive these notifications they must add Chrome notifications to this widget.

Apple has its own proprietary beacon technology, iBeacon, which, if one was to compare, would be more like Eddystone-UID than Eddystone-URL. That is, it broadcasts an ID rather than a URL (a 16 byte UUID and major and minor ids of 2 bytes each [pdf]). To use iBeacon, you need to have an app installed. iOS does not currently support the triggering of URLs via iBeacons.

So although the Google’s Beacon platform supports Apple’s iBeacon technology, until a beacon can trigger a web URL on iOS, as opposed to launching an app, then we’ll always be looking at a suboptimal user experience on iOS, and a headache for beacon project implementors as workarounds are explored.

A very Google platform

While the enhancements to Eddystone are beneficial, and the Beacon Dashboard, and platform as a whole, provide many benefits over the Eddystone-URL Physical Web, it’s also apparent that these also happen to serve Google very well by keeping them involved all the way in the entire Beacon stack, and in a position to track activities.

It also feels like these evolutions make it less likely that other companies will be able to compete because there’s so much more to it now. The simple open charm of the first incarnation has been lost a little—it’s feeling very “Google” now—useful, but with a hidden cost.

The Eddystone-URL Physical Web vs Nearby physical web

This completes our exploration of Google’s BLE beacon platform. We saw two different approaches to setting up your BLE beacons, and noted the messaging dicohtomy of the Eddystone-URL Physical Web vs the Nearby physical web. The Eddystone-URL approach is the easier of the two to get started with, not requiring Google services to get up and running. On the other hand, informal testing during the research for this article suggests that the notifications from BLE beacons set up as Eddystone-UID via Nearby and the Beacon dashboard show up more reliably than when set up with the Eddystone-URL approach.

The Nearby approach will scale better too, since it has a centralised and remote way to manage and monitor your beacons. This advantage comes at a cost though, in terms of set-up complexity. Another drawback is that you will be relying on Google services for your application, and this can be problematic if there are any issues with that service, as we saw with the global muting of nearby notifications between September and November 2016. This obviously represents a risk for commercial applications. Eddystone-URL has fewer moving parts and dependencies.

The Beacon platform can be confusing to newcomers. This is in part because of overlapping APIs, and multiple approachs to achieving the same goal, and also in part due to the messaging. The Physical Web is messaged as a very specific thing: BLE beacons broadcasting in Eddystone-URL. But really the physical web is more than this. Once you get passed this confusion, you’ll find a comprehensive beacon platform to power your beacon project, whether you go for the simplicty of Eddystone-URL or the power of Nearby and Eddytone-UID.

Main image: Dirk Duckhorn

Leave a Reply