Back in August 2013 Facebook announced its Internet.org plan to bring Internet access to the next billion people in developing countries.

Most of the media coverage has focused on whether or not it violates net-neutrality, if it’s creating a two-tiered Internet, or if it’s just another walled-garden with Facebook as gatekeeper. In this post, we set aside those issues for the time being, and focus instead on the technical guidelines for getting a site included in Internet.org.

The Internet.org Platform

The Internet.org Platform describes itself as:

an open platform that allows any company to sign up to be zero rated, wherein customers won’t have to pay for accessing these sites, and websites will have to be approved to be allowed in.

After global criticism to the closed and allegedly net-neutrality violating nature of Internet.org, Zuckerberg opened up the platform to any developer whose website meets the technical guidelines; and the set of technical guidelines was also published.

Not only did this open the platform up, but, via the technical guidelines, it gave us a glimpse into what Facebook considers to be mobile-friendly.

Internet.org technical guidelines

Internet.org focuses on supporting simple lightweight websites, with an emphasis on feature phones.

the majority of people in emerging markets still have feature phones. To ensure that Internet.org is accessible to all, we focus on supporting lightweight mobile websites.

There is also an emphasis on efficiency: infrastructure and data must be efficient so that operators can sustain infrastructure. This means high-bandwidth, VOIP, video and even image-heavy sites won’t be included.

So, getting to the nitty-gritty, according to Internet.org, mobile websites must work without the following:

- JavaScript

- SVG images and WOFF font types

- SSL/TLS

- iframes

- Video and large images

- Flash and Java applets

Interestingly, this list reads as if it was straight out of the W3C mobile web best practices (MWBP) which some of us here at mobiForge helped draw up back in 2006.

While some of the details of these best practices might not be as relevant as they used to be (for example, smartphones can handle more than 20KB) most of them are still sensible things to implement, even if the precise values of parameters have changed (keeping page size low is still very important and desirable, even if the acceptable limits have increased).

Let’s take a closer look.

How the Internet.org Platform works

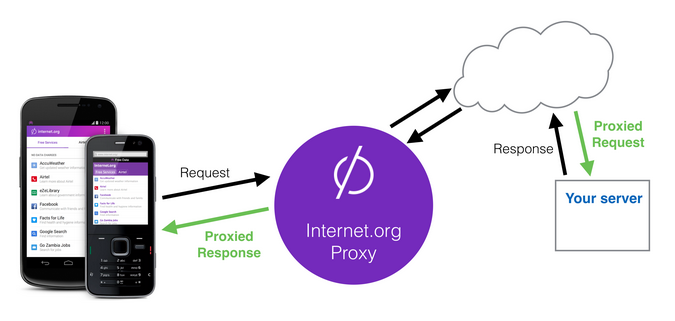

All ‘zero-rated’ websites must be submitted to and approved by Internet.org. If they pass the technical requirements they are ‘zero-rated’ and browsable for free.

Approved websites browsed via Internet.org app are pushed through the Internet.org transcoder proxy:

This will have the effect of compressing and stripping assets to fit them to the user’s device.

JavaScript

Internet.org approved sites must work in the absence of JavaScript. The motivation for restricting JavaScript is that it may not work on low-end devices. This requirement corresponds with the W3C MWBP OBJECTS_OR_SCRIPTS, which advises [not to] rely on embedded objects or scripts.

JavaScript is also difficult to reliably proxy-transcode (see what the proxy/transcoding browser Opera Mini has to say about JavaScript support). So another factor is that the Internet.org proxy may simply not be able to faithfully work with JavaScript-reliant sites, and any such site may not work very well, or even at all, when proxied.

This is bad news for all JavaScript-rendering framework sites, as they will be excluded from participation. This means, AngularJS and ReactJS sites are going to be left out in the cold.

SSL/TLS

Sites that rely on SSL/TLS/HTTPS will not be able to participate. That is, only insecure sites will be included. This is the one technical requirement that is not really about mobile-friendliness—even feature phones have been able to handle HTTPS for years. The motivation for this requirement is that the Internet.org proxy can’t work with end-to-end encryption. So the price of the proxy is privacy!

iframes

Frames can be generally problematic for mobile, and may not be supported at all on some feature phones, and so are excluded from Internet.org. This corresponds to the W3C MWBP NO_FRAMES guideline. Usability problems associated with frames can be found here.

Video and large images

This restriction is all about bandwidth and page weight. Videos and images are the heaviest components of the web, so video and image-heavy sites will be slow to load, and can clog up vulnerable networks. This corresponds with a number of recommendations of the W3C MWBP:

- LARGE_GRAPHICS: Do not use images that cannot be rendered by the device. Avoid large or high resolution images except where critical information would otherwise be lost

- OBJECTS_OR_SCRIPTS: Do not rely on embedded objects or script.

- PAGE_SIZE: Ensure that the overall size of page is appropriate to the memory limitations of the device.

Flash and Java applets

Flash and Java applets are also excluded from Internet.org sites. This is because they are very unlikely to run on feature phones. This was also covered by the MWBP OBJECTS_OR_SCRIPTS not to rely on embedded objects or scripts.

Internet.org and the universality and decentralization foundations of the web

On the face of it, these guidelines mostly make sense for anyone striving for mobile-friendliness, with the exception of banning HTTPS sites of course. So why the global backlash?

To put things in context it’s useful to remind ourselves what Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web, had to say about universality of the web [pdf]:

The primary design principle underlying the Web’s usefulness and growth is universality. When you make a link, you can link to anything. That means people must be able to put anything on the Web, no matter what computer they have, software they use or human language they speak and regardless of whether they have a wired or wireless Internet connection. The Web should be usable by people with disabilities. It must work with any form of information, be it a document or a point of data, and information of any quality—from a silly tweet to a scholarly paper. And it should be accessible from any kind of hardware that can connect to the Internet: stationary or mobile, small screen or large.

Tim Berners-Lee also mentioned decentralization as key ingredient of the web:

Decentralization is another important design feature. You do not have to get approval from any central authority to add a page or make a link.

Although Facebook has bowed to pressure and ‘opened’ up the platform, it’s still not truly open, or universal. There are technical guidelines, but Facebook is the sole arbiter in respect of approving sites. So users of the service will not be able to access all sites equally. Sure, users are free to access any site they want outside of Internet.org, if they can afford to pay for it. And it’s clear that the Internet.org proposition violates decentralization too, because of its approval process and proxy setup.

Groups around the world have been crying foul, and 67 rights groups from all around the world have penned an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg, voicing their concerns:

[W]e are deeply concerned that Internet.org has been misleadingly marketed as providing access to the full Internet, when in fact it only provides access to a limited number of Internet-connected services that are approved by Facebook and local ISPs. In its present conception, Internet.org thereby violates the principles of net neutrality, threatening freedom of expression, equality of opportunity, security, privacy and innovation

Facebook’s responses and guidelines have been underwhelming at best, and arguably contradictory to the project. First, one of the guidelines is that Internet.org sites should encourage exploration of the entire Internet. This is of course impossible for most of the people at whom Internet.org is aimed, as they will have to pay to explore any of the Internet hosted outside of Internet.org, which is most of the Internet.

Facebook also claims that the project will encourage new users to start to pay for wider services on the Internet:

We are convinced that as more and more people gain access to the Internet, they will see the benefits and want to use even more services. We believe this so strongly that we have worked with operators to offer basic services to people at no charge, convinced that new users will quickly want to move beyond basic services and pay for more diverse, valuable services.

Once again, this seems contradictory. Isn’t Internet.org aimed at some of the poorest people in the world?

Internet.org: a mobile-friendly walled garden

Apart from the security issue, the Internet.org technical guidelines make sense in terms of making the Internet more accessible to the widest audience possible, and sites are pretty much guaranteed to run on feature phones. They echo a lot of the things we’ve been saying on this site for years. Internet.org talks about progressive enhancement too, so experience on higher end devices is not necessarily degraded for the benefit of feature phones. Performance and page weight are top priorities, with a maximum of 1MB for resources. While this is still a bit high, the final page is being squeezed through a proxy server, so even sites with large resources will be transcoded into something more digestible anyway.

Unfortunately, due to the opt-in for approval nature of included sites, it is still essentially a walled garden: even if your site would pass the guidelines, it won’t be included. Perhaps Internet.org could do better here by going out and crawling the web and automatically including everything that’s compatible. In any case, walled gardens in general do not have a record of successfully thriving over the history of the web; does Facebook know better this time round?

Whether or not Internet.org as an initiative prevails, it’s good to see that Facebook is raising developer awareness of web performance issues. Indeed, this is also Facebook’s stated reason[pdf] for the introduction of its new Medium-like Instant Articles, although it does of course have a lot to gain by becoming the web’s default publishing platform. Still, the emphasis on performance is welcome.

Leave a Reply