With the roll-out of LTE networks across the world over the past few years, and all the associated excitement about super high-speed mobile connections, it can be easy to forget that slow-to-grindingly-slow is the normal connection speed across large parts of the world. In Asia Pacific, for example—the world’s fastest growing mobile market—65% of all connections were 2G only in 2013. In Western Europe, approximately 30% of all connections in 2013 were 2G only; and by 2019 LTE will account for (only) 50% of the market. While 2G-only connections are expected to decline as more networks across the world gain 3G and 4G capabilities, by 2017 it will still account for 47% of the total.

In North America and Western Europe, 3G and 4G dominate, but at the lower end of the market, consumer plans more often than not come with a limit on the amount of data that can be transferred over these high-speed networks. These limits can be low—on Straight Talk in the US, for example, $30 a month gets you only 100MB of data; Germany’s Otelo offers 300MB for €7.99 a month. Once a limit has been reached, throttling or charging (often at a punitive rate) is the norm; this means that even in these developed markets, and even with ‘high-speed’ plans, a proportion of consumers don’t have constant access to fast mobile internet.

A rather large phone bill (source: Flickr)

As we’ve noted before on mobiForge, page weight has been on a fairly constant upward trajectory over the past number of years. In November 2014, the average desktop homepage was a hefty 1.9MB. Combine network latency, 2G connections, restricted data plans, and data-heavy websites, give them a stir, and you’ve got a slow, frustrating mobile web experience for an awful lot of users; a reality that has been rather obscured in all the excitement about 3G and 4G networks.

When slow means really slow

Whether a provider will throttle speed or charge per MB over a certain limit varies from market to market, with throttling being more popular in some (for example in the US and Germany) and charging more popular in others (the UK and Australia).

In those markets where throttling is common, speeds can be reduced to as low as 32kbps. Vodafone in Spain, on its Vodafone Yu plans, does this, for example. In general, speeds are reduced to either 32kbps, 64kbps, or 128kbps, or to a 2G rate of transfer.

| Country | Carrier | When limit is reached? |

|---|---|---|

| United States | AT&T | Speed throttled to 128kbps |

| United States | Virgin Mobile | Speed throttled to 2G |

| United States | Boost Mobile | Speed throttled to 2G |

| United Kingdom | Vodafone | Charging |

| United Kingdom | O2 | Charging |

| United Kingdom | Orange | Charging |

| Germany | Otelo | Speed throttled to 64kbps |

| Germany | Lidl Mobile | Speed throttled to 64kbps |

| Germany | Vodafone | Speed throttled to 32kbps |

| Spain | Vodafone | Speed throttled to 32kbps |

| Spain | YoIGo | Speed throttled to 64kbps |

| Spain | Carrefour Móvil | Speed throttled to 128kbps |

| Spain | Tuenti Móvil | Charging |

| Italy | TIM | Speed throttled to 32kbps |

| Italy | Fastweb | Speed throttled to 64kbps |

| Ireland | Meteor | Charging |

| Ireland | Vodafone | Charging |

| Ireland | Three | Three ‘reserve the right to limit your Service’ |

Some of the approaches taken by carriers in various markets once a data limit is reached

Is a throttled connection usable?

At first glance these numbers might suggest that one should just give up—the web is simply unusable at these speeds. However, things aren’t necessarily that bad, or rather, they don’t have to be. On a throttled connection (or indeed a pay-per-MB connection) the number of bytes your site is pushing down to a device becomes crucial. Too many bytes on a throttled connection, and your site simply becomes unusable.

Consumers can take matters into their own hands by using a transcoding browser like Opera Mini, or an online transcoder like Google’s Web Transcoder (yep, it’s still alive!).

While Opera Mini is a wonderful browser, and has helped over 300 million users on slow connections, or low-end devices, or in censored territories, to have a better web browsing experience, turning to transcoders comes with its own set of problems. More complex interactions, that require javascript for instance, (e-commerce, form filling, and even logins) might not work with a transcoder sitting between your site and your visitors.

And as many websites become more app-like it’s not getting any easier for transcoders: with sites employing plugins and building blocks like jQuery, Angular, and Polymer, app-like websites are becoming more and more mainstream.

With transcoders you also lose some control over the design of your own site, since a transcoder, by its very nature, must make a best effort to squeeze and rejig on-the-fly the site being visited to fit the user’s device. Despite its large user base, Opera Mini is often omitted from browser testing plans.

Security is worth mentioning here too. While perhaps an acceptable risk for many a casual browser, having your sensitive data relayed via a proxy is not ideal. It really boils down to whether you can trust the middleman to not compromise your data.

Transcoders attempt to address the problem by filling the gap between the capabilities of the device and the technologies of the web. They would not exist in an ideal web world where every site could satisfactorily support every device on every connection in every territory. Unfortunately, a large portion of your visitors may not know what a web transcoder is, or have ever heard of Opera Mini, let alone have it installed (exceptions of course being in markets where it comes preinstalled on popular devices such as the Nokia Asha). So, if you are relying on your bandwidth-challenged visitors to have a particular browser installed before they can view your site, then you’re not doing yourself any favours.

What does this mean for developers?

Whether you want or need to cater for users on slow or very slow connections will depend on your business, and the user base of your site. But, if inclined, developers and site-owners can indeed accommodate these users. One approach is to implement bandwidth detection. The idea is simple: if a slow connection is detected, then a smaller payload can be delivered to the device, for example by compressing image assets, or dropping or adapting JavaScript and CSS. On faster connections, higher quality assets and more feature-full markup and scripts can be used. Image quality and UI overhead are traded for speed, and this can mean the difference between a usable and unusable site.

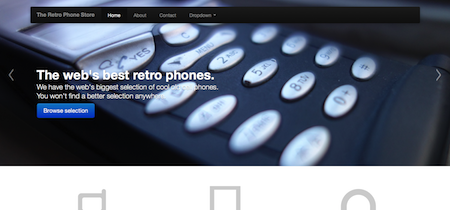

Google uses bandwidth detection to decide what to show users

Bandwidth detection is being implemented all around you: Google’s doing it (try image search on a slow connection), Facebook’s doing it, and you can do it too! In the sample implementation in the article mentioned above, a ~40x saving in page weight was possible without degrading the user experience. To the contrary, this huge page weight saving will very much enhance the experience of users on slow data connections. The results are illustrated below.

Site before optimization on different devices

|

|

|

|

Desktop

1360 x 768 1,027 KB |

iPhone

320 x 480 1,027 KB |

Nokia 6300

240 x 320 1,027 KB |

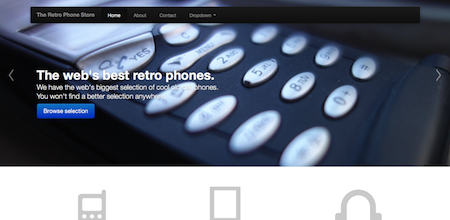

Site after optimization on different devices

|

|

|

|

Desktop

1360 x 768 1,027 KB |

iPhone

320 x 480 153 KB |

Nokia 6300

240 x 320 25 KB |

Some of the data behind these images are shown in the table below. See the article for more details.

| Original site | Add image resizing | Adaptive JS & CSS | Adapt to connectivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Page size | Load time | Page size | Load time | Page size | Load time | Page size | Load time | |

| iPhone 3G | 1027 KB | 14s | 253 KB | 7s | 253 KB | 6s | 153 KB | 5s |

| iPhone GPRS | 1027 KB | 2m 30s | 253 KB | 40s | 253 KB | 40s | 153 KB | 25s |

| Feature phone (2G) | 1027 KB | ∞ | 203 KB | 35s | 87 KB | 25s | 25 KB | 12s |

Conclusion

It is often assumed that smartphones and LTE equates to fast and capable mobile internet connection, and that slow-speed and low-bandwidth are confined to emerging markets. This is not always true in the highly competitive world of data-plan marketing and budget-conscious users. Throttling ‘high-speed’ data connections after a certain limit has been reached is a common practice across carriers worldwide. This means a portion of your visitors will be using a very slow connection, even in developed markets. If you’re operating in a market where throttling is common, then not adapting to bandwidth-challenged customers might well be a market limiting decision.

Leave a Reply