Introduction

There could hardly be a more perfect privacy invasion machine than today’s smartphone. It’s with you at all times, it knows precisely where you are, it can see and hear you and it knows exactly what you are doing much of the time.

If data is the pollution of the digital age then your smartphone is an overweight 1970’s V8 gas guzzler with asbestos brake pads, a leaky freon-charged AC system, burning leaded fuel as it barrels down the highway: you are silently spewing out reams of potentially harmful data all day, every day.

Vision vs. reality, 1971 — “Something to believe in.”

Newsweek considered privacy to be a vexing enough topic to tackle it back in July of 1970. The subtitle of this article is “Snoops, Bugs, Wiretaps, Dossiers, Data Banks — and Specters of 1984”.

Newsweek, July 1970. An alarmist headline then, quaint and naive now.

In this article they lamented that:

..the elemental right to privacy stands in serious danger.. concerned Americans are in fact asking whether it may not be dying.

And go on to say:

individual Americans have begun to surrender both the sense and reality of their own right to privacy.

How far we have come; it all seems quaintly naive now. You can read the full article here.

Unfortunately, like some forms of pollution, privacy violations are invisible until you have a serious problem. In this article we’ll examine where we are today particularly with the aspects of privacy that are unique to mobile, rather than covering mass NSA spying, since this topic has been well-covered elsewhere.

Why Should we Care?

It’s worth asking the question why privacy is an issue at all. Should we care that our mobile app usage is being monitored and that our web activity is tracked? The short answer is yes.

Before we dive into this some terminology definitions as they apply to this context are useful. Broadly, you can think of privacy, confidentiality and security as concentric layers, as follows:

In the context of this article, the terms can be defined as follows.

- Privacy

- The right to keep data on me restricted to myself or parties I trust, or if I choose to share it in exchange for goods or services, the right to expect that my data will be treated as confidential.

- Confidentiality

- The commitment to hold private data belonging to individuals in confidence, and not distribute or use in the delivery of goods or services to others, except by explicit agreement of the individual.

- Security

- The processes and mechanisms to protect private data, being the means to assure confidentiality is maintained, so that no breach of privacy can occur.

The reliably clear-thinking Bruce Schneier points out that one of the biggest problems with personal data being tracked and stored is not the primary use of this information but rather the secondary and subsequent uses of that same data. As an example, you necessarily generate a data trail with your local supermarket when you make purchases there, and that’s fine (the primary use) but data inevitably leaks or is stolen afterward and that’s where the problems start. We may not care if our supermarket knows our buying patterns but would you want your health insurance company to know about the medication you buy or your diet? It is already known that insurance companies make use of such information if they can and there are already marketplaces for purchasing this kind of information en masse. Because there is a market for this information there is an incentive to gather it, legally or otherwise. Mobile takes this pre-existing situation and adds a potent extra set of ingredients to the mix.

Three Layers of Privacy Leaks

There are three main layers to the privacy story on a today’s smartphone.

- Cellular network

- Native apps

- Mobile web

I’ll go through each one in turn.

The Cellular Network

The basic cellular phone privacy issues are fairly well understood at this point so I won’t spend too much time on them here except to hint at just how invasive even this basic level of information is when captured in bulk. This is a good example of data that consumers assume is confidential, but in fact is more widely available than they think, and hence privacy is compromised.

Photo from flickr user pulpolux

The fact that the cellular network leaks information about you shouldn’t be surprising: in order to work at all the cellular network necessarily needs to know where you are, at least to the closest cell. By correlating the different signal strengths perceived at each tower you can get a pretty good idea of where someone is. The personal location data is a side-effect of the design. In some countries laws have been imposed on mobile operators around making caller position known in the event of calls to the emergency services. Mobile operator logs have already been used to prove/disprove crimes.

What may be surprising however is just how much insight can be gained into a person just by looking at this data when it is captured in bulk. This was brought dramatically to light recently when German politician Malte Spitz decided to find out just what his mobile operator knew about him from his mobile phone activities. You can see a quite disturbing visualisation of a two day period of these in this YouTube video.

Malte Spitz drives near Erlangen, as revealed by Deutsche Telekom records

There has been debate about how your phone can be tracked even if it is off. Interestingly, both Nokia and Samsung have said that they don’t know how this is possible but some engineers disagree, pointing out that there’s no way to know for sure what is happening in the baseband software of phones since it is manufactured by a third party. It’s quite possible that spy agencies are working with baseband chipset manufacturers, just as they have been working with security standards groups to weaken algorithms. If you really want to be sure put your phone in a cocktail shaker and put on the lid, or take out the battery, if you can.

Native Mobile Apps

Native mobile apps are arguably the most insidious invasions of our privacy ever invented. A native mobile app brings three characteristics together in a particularly noxious combination:

- Full access to the phone hardware and sensors within the constraints of the operating system

- Full network connectivity

- No oversight or transparency

Let’s look at what apps can get access to:

- GPS. Apps can know your location via GPS (and GLONAS), WiFi and cellular tower ID. Most phone OSes will show an indicator to let you know that a GPS lookup is happening but it may not be clear which app is actually doing it. Cell tower and WiFi location lookups are not visible to the user. Many apps that seem like they shouldn’t need your current location capture it anyway.

- Network stack. An app can send whatever it likes to any location it wishes. Users have no way to check this. To add insult to injury the end user may have to pay for this network traffic depending on the nature of your data plan.

- Your address book. Apps get full access to your address book though operating system APIs, though users are often informed of this in modern OSes. This famously came to light recently with the Path app which was using customer address books for nefarious purposes.

- Camera. Clearly apps can use your devices camera but most devices will make it very clear that this is happening to help protect the user. On desktops and laptops the camera has an indicator that is (supposedly) hardwired to its operation but most phones have no such light.

- Microphone. Your phone can be listening to you or your surroundings and can do what it choses with the result. The most recent example of this was the now-defunct Color app, which listened to your surroundings (without telling you) to gather contextual information.

- Accelerometer / gyroscope / compass. These are less invasive of the user’s privacy, but can reveal whether you’re on the move, driving vs. walking etc. The angle of the device can be used to infer quite a bit: 100% horizontal with no other accelerations likely means the device is on a table and you’re sedentary; an angle between (say) 120° and 160° from horizontal probably means you’re lying on your back in bed or a couch. These sensors also allow for fingerprinting since each one has slightly different imperfections that distinct enough to be uniquely identifiable.

- SMS. Most smartphone OSes offer access to the full set of SMS folders

- Calls. As with SMS, smartphones allow apps to interact with the call history

- Fingerprint sensor. The iPhone 5S fingerprint sensor is separated by hardware from the rest of the phone and not available to apps, but other implementations may not have the same level of security.

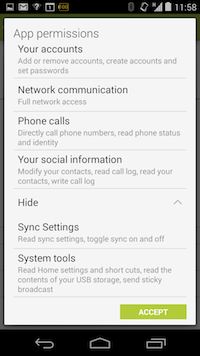

Let’s take a look at one app in particular, Facebook on Android in this case. Here are the permissions it requests upon installation:

Facebook app permissions requests for Android. Do you really want it knowing all of that about you?

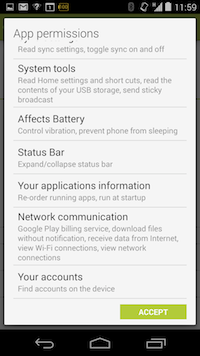

In addition to the features mentioned above, Facebook is requesting access to your running apps list, download files without notifications, look at the various accounts you have configured and ability to write to your call log. I don’t mean to pick on Facebook here and I have no doubt that these permissions are grounded in legitimate features of the app, but it also feels like privileges that can be abused later, the thin end of a very thick wedge. Some apps appear to make more unreasonable requests. The Brightest Flashlight Free app requests permissions for location, camera and phone status amongst other things.

Free flashlight app comes at a high price.

This particular app found itself at the centre of an FTC investigation and eventually settled. You can read the details in this Guardian article.

And it doesn’t stop there. In addition to the information available from sensors, many companies use analytics services to track customer engagement within the app to a very fine level of detail. As an example, on the Economist app on iOS, every single article you read triggers a ping back to an analytics service. While this could be explained away as merely measuring of engagement it feels a little intrusive, not to mention extremely annoying, when the supposedly already-downloaded page blocks on a network event that sometimes fails. Do you really want people to know how long you spend on each page? What if the article you’re reading isn’t something you would want people to know about? Obviously this is a routine practice on the web but I believe that many people understand that web browsing is an “online” event and hence there is some expectation that this may be happending whereas with apps there may be more of a belief that what you are doing is private.

So far I have mentioned just the basic features available to all apps but bear in mind that specific apps will often know much more about you from the data you feed to them e.g. RunKeeper knows how much exercise you are getting and so on. Again, the danger isn’t so much with the primary use of the data (tracking your runs in this case) but with the confidentiality of this data—what it can be used for afterward, either intentionally or otherwise.

Mobile Web

Mobile web users are open to many of the privacy invasions available to native apps, but there are two reasons why the situation is better, and one reason why it is worse.

The privacy situation with mobile web is less serious for two reasons. Firstly, the browser is significantly more heavily sandboxed than native apps and hence has much more limited access to the underlying device than do apps, despite some welcome ongoing improvements to browser APIs that offer access hardware and OS features. Currently, mobile browsers have access to a limited set of features, typically something like the following:

- Accelerometer / gyroscope / compass

- GPS

- Camera

- Battery status (in recent browsers)

This set of features that are accessible directly by the browser is evolving rapidly thanks to the efforts of the W3C’s Device APIs Working Group.

Secondly, the web is inherently transparent because, in effect, every web page or webapp is open source. If you really wanted to you could look at the source of the page/app to see exactly what it is doing, though you can’t tell what happens with the data once it leaves your phone.

But these two privacy improvements are offset quite a bit by the inherent web-like nature of browsing: you are being tracked from site to site by JavaScript-based beacons and third-party cookies that are continuously building a profile of you as wend your way around. This is no different than desktop web surfing, of course, except that your mobile browser can know much more about you: searching for a restaurant when your phone knows you’re in downtown Manhattan carries a much stronger contextual signal than the same search performed from a desktop PC whose location is unknown.

The good news is that you can prevent much of this tracking by disabling third-party cookies on browsers that support it (not supported by Chrome, but disabled by default in Safari). Secondly, if you’re really concerned about mobile web privacy you can disable JavaScript to prevent code running at all when you visit a site but bear in mind many sites will not work well or at all without it. There are ways for sites to get around third-party cookie restrictions (Google does this via a range of browser hacks) but this is still quite rare and getting enough attention that the loophole may get closed.

Even with cookies turned off, however, it is worth knowing that there is a good chance that you are still identifiable through a combination of browser introspection and by examining the HTTP headers that are sent with every request. You can try this out yourself with the EFF’s Panopticlick experiment.

Future

So, given the huge scale of privacy leaks that are possible with our indispensable mobile gadgets, what hope is there for any improvement in our situation?

To understand where privacy and mobile is going you have to understand the motivations for privacy intrusions in the first place. There are three main reasons why companies seek to gather data on people:

- As part of a free or freemium business model that uses advertising to make up for a “free” service

- Tracking usage and engagement

- More nefarious uses e.g. spamming people in your address book to drive adoption

As consumers we have collectively bought into the current situation where advertising (and hence privacy intrusions) are the business model for the web and many apps. We seem to be unprepared to pay for content and services online, therefore advertising has taken the place of payments, with attendant intrusions into privacy to make these advertisements effective. Many people baulk at spending even a fraction of the price of a cup of coffee on an app. If we’re not prepared to pay for online content and services is it reasonable to expect privacy of your data from advertisers? Can you have your cake and eat it? On the one hand this model is just an evolution of that used to fund free content on TV / radio, but on the other hand the advertiser now has significant extra insight, and consumers haven’t yet realised this. The landscape has evolved asymetrically …in favour of the advertisers.

The only real way to make this class of privacy intrusions less attractive is to remove the incentive to do so by paying for services you consume and choosing paid services over free ones.

The second and third use cases are more difficult. The best solution is awareness and oversight. It seems likely (inevitable?) that legislation will come to bear on the industry: companies will at some point be forced to publish exactly what data they are capturing from users, where it is stored, how it is used, and by whom. Google’s Play store has taken a step in the right direction here by disclosing requested permissions of Android apps but its warnings are still too abstract for many people and, perhaps more importantly, don’t communicate what is being done with the information thereafter and how it is being secured. Obviously exercise tracking apps need to know where you are to function but what else are they doing with the information about you? Is it being sold onwards? Is it being stored safely? Is the stored information really deleted when you delete your account? Who knows.

Some sort of legislation seems inevitable because the data breaches are just going to get bigger and more dangerous as more and more private information is stored and more ultimately leaks or is stolen. Legislation invariably trails technology, and has done so for some time. There is evidence that law makers are beginning to catch up (e.g. the settlement of Brightest Flashlite Free with the FTC) but technology is likely to stay ahead, as it has always done.

It’s not yet clear how this story is going to play out but, right now, we’re still mostly in the blissful ignorance stage, and still heading in the wrong direction. As with motorists back in the early 70’s, so it is now: we’re barreling down the highway, largely oblivious to the problem we’re building.

Note: phone as data repository

For many people the phone is now their PC. For this reason many of us store bank details, passwords, SSNs, Dropbox folders, website logins etc. in our phones. This isn’t a privacy issue per se but it’s worth remembering just how much you have to loose should your mobile phone fall into the wrong hands. I would strongly recommend that you use a secure password vault app if you wish to store private details on your mobile device. Don’t rely on lockscreen passwords or obfuscated notes in fake address book entries.

EDIT 5/12/2013

Added privacy diagram and edited definition of terms.

UPDATE 27/1/2014

Since publishing this article yet another NSA-related news has come to light which suggests that the NSA has a very strong ability to mine data from native phone apps. You can read coverage of this in The Guardian. The news is about as bad as you might expect:

Depending on what profile information a user had supplied, the documents suggested, the agency would be able to collect almost every key detail of a user’s life: including home country, current location (through geolocation), age, gender, zip code, martial status – options included “single”, “married”, “divorced”, “swinger” and more – income, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education level, and number of children.

Something tells me we haven’t heard the end of this particular story.

Leave a Reply