Launched in 2014 Google’s Physical Web project promised much, but seems to have died a quiet death over the last few months. This post takes a look at what the technology promised, and the speed bumps it hit along the way that may ultimately prove to have derailed it.

Everything is a tap away

Google’s Physical Web project was conceived to enable smartphone users to interact with physical objects and locations through the use of beacon technology. We have written extensively on how the technology works and how to set it up here, but a brief synopsis on the concept follows:

Based on the presence of small devices known as beacons, placed on or in physical objects, a user can receive a notification on their handset when within range of the beacon. The notification contains a link to a related web resource. You click the link and the related web resource opens in your browser. Simple, yet powerful.

The beacons themselves use a low energy version of Bluetooth technology to broadcast the data, which in turn can be picked up by compatible devices. Beacons are inexpensive and widely available, offering up the possibility for the physical world to be ‘marked up’ by the inclusion of these devices transmitting an additional layer of information to all who wish to receive it. This opens up a whole host of interesting use cases for users to interact with objects in the physical world that may have been up until now, unconnected.

Google’s Physical Web project site gives the following examples of how it might be used:

- A bus that could alert users of its next stop.

- A city rent-a-bike service could enable users to sign up on the spot.

- A home appliance could offer an interactive tutorial.

- An industrial robot could display diagnostic information.

- A mall that could offer a map.

Other cool examples we came across included Virgin Atlantic check-in (which works on Apple’s iBeacon standard), or interactive restaurant menus that give you more information on today’s specials, provenance of your food, wait times. Even the ability to help a lost pooch find its owner via a beacon in its collar!

Despite the undoubted potential of the Physical Web, all has not been plain sailing for the initiative. One of the main issues confronting the Physical Web’s adoption was initially the need to install a native app to be able to receive broadcasts of URLs. The project got a boost when support was added to the Chrome browser first on iOS, later on Chrome. This was a pivotal development as it meant that a separate app install was no longer needed to receive notifications of URLs being broadcast by beacons. Notifications could be received using the widely installed (at least on Android) Chrome browser as the delivery channel. Notifications would show up in the Notifications Manager when the user accessed it, or in the Today tray in the case of iOS. Theoretically, at least, the Physical Web was cross-platform. The technology’s future looked bright in 2016, when the Physical Web and beacon technology was center stage at the annual Google IO developer conference.

The real potential for the PW is smart devices, not retail coupon announcements

— Scott Jenson (@scottjenson) June 21, 2017

The momentum continued when support was added to the Android platform itself via the Nearby Notifications. This approach offered a way for developers to mass deploy beacon technology and manage everything from a centralized dashboard based on Google’s Beacon platform (the big brother of the Physical Web project). But it was this development that brought the technology directly into the OS that signalled the Physical Web project’s demise.

Development issues

Although deployment of beacons on Google’s platform is a reasonably straightforward (albeit convoluted) process, there are several issues that may hold it back from achieving mass adoption.

In the first instance, there are several versions of the Eddystone communication protocol, and the Physical Web relied on the link broadcasting Eddystone-URL version. Many developers have reported uneven results while attempting to deploy this most basic Eddystone URL broadcasting approach.

Further complications arose in September 2016 when beacon notifications set up to run using the Android OS Nearby notifications feature were muted for 2 months because of a bug in Google Play Services which caused notifications to persist. There were also some reports of duplicate notifications from Nearby and Chrome.

The biggest single challenge the Physical Web project’s survival has undoubtedly been the withdrawal of support from the Chrome browser.

Physical Web RIP

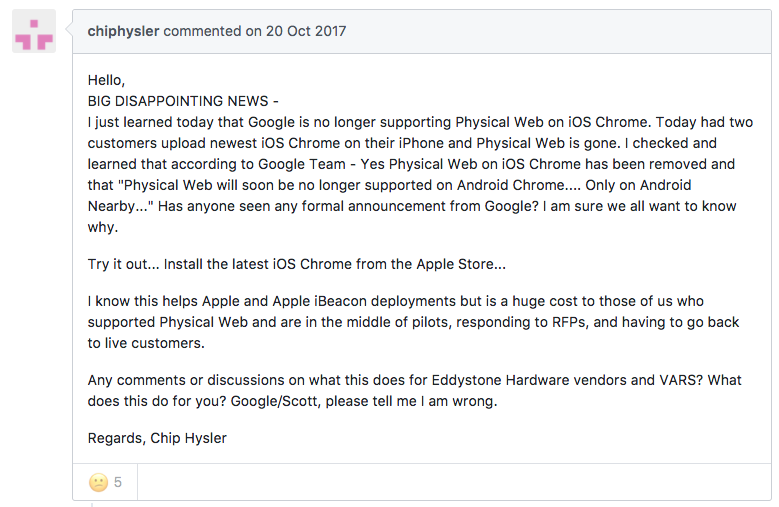

At last year’s I/O development conference, beacons and the Physical Web were conspicuous by their absence on the speaking agenda. Just a year previously they had been center stage. Then came the killer blow in October when, Google abruptly ended support for the Physical Web, removing the support for beacon notifications from both Android and iOS versions of Chrome. This triggered some ire from developers who had or were in the process of deploying Physical web projects for customers.

So no more cross platform notifications for iOS users with Chrome installed. It’s worth pointing out that Chrome usage on iOS is less than 5% of iOS browser market. And you’ve still got iBeacon (though that requires an app).

Nearby killed the Physical Web

The Physical Web project made it easy to deploy beacons on an open, distributed standard. It has now been superseded by Nearby notifications which requires developers to use the Google Cloud platform. And while the APIs that underlie Nearby support more functionality than the Physical Web project – such as peer to peer messaging and connectivity for devices in proximity to each other – there is a distinct sense that this comes at the cost of some of the openness and decentralized model that the Physical Web project championed.

Beacons: live long and prosper?

To be clear, beacon technology has by no means gone away. But users and developers will still have to make up their minds on whether it goes mainstream. For the proximity notifications envisaged by the Physical web project at least, many feel its current Android implementation is hamstrung. Built-in checks and balances to control intrusiveness, known as the backoff policy limit how visible notifications are. Each time a user dismisses a beacon notification, the OS progressively suppresses further notifications until they are completely disabled. For the average user, there may not be enough traction behind the idea of engaging with beacon notifications to stop this happening. A user’s experience of Nearby notifications may seem somewhat random unless a user knows exactly what is going on. And how many of these messages will truly be relevant? What’s more, it’s placement doesn’t bode well as it’s really buried and to get an app icon for it involves a few steps.

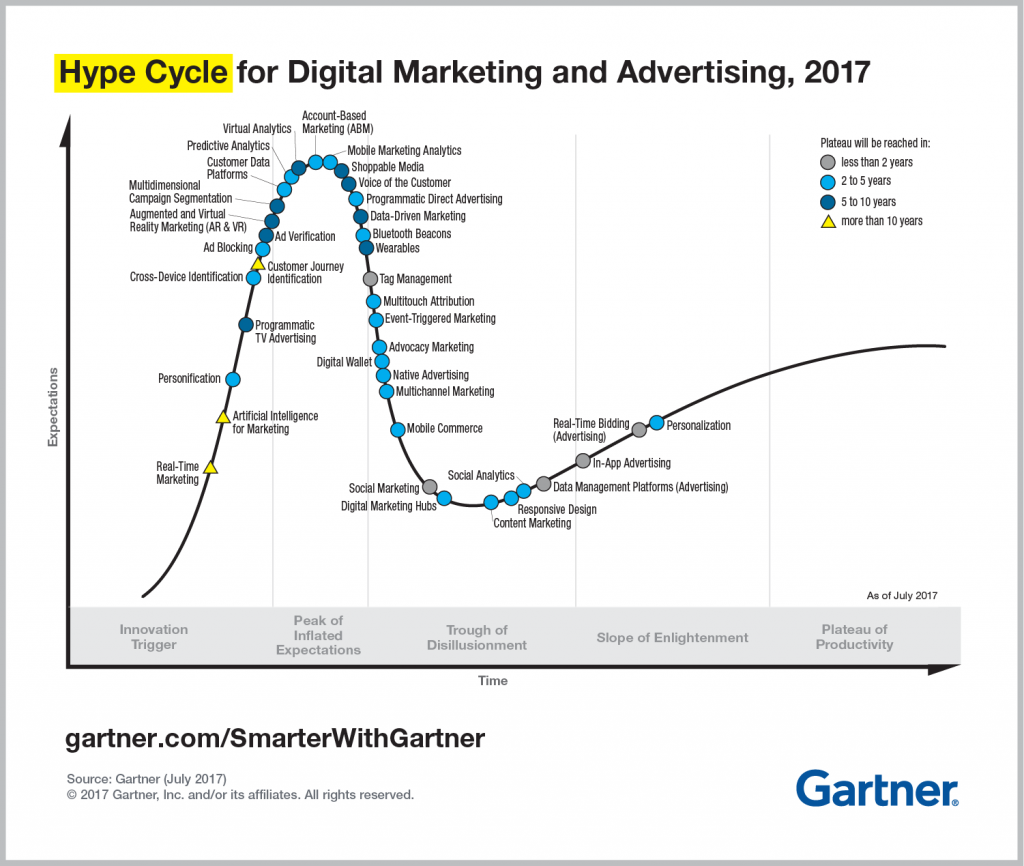

Beacons are not the first proximity technology to emerge. QR codes have persisted despite the hassle of having to fire up a scanner to read them. Support for NFC tags has just been added to iOS11. According to the Gartner hype cycle, Bluetooth beacons are getting set to enter the trough of disillusionment. Only time will tell if its a long term initiative that Google will support.

Leave a Reply