With Facebook hogging most of the headlines over the last few months, Google has been quietly shoring up its assets and getting its ducks in a row.

Facing a $5 billion fine by EU regulators for breaking antitrust laws with the Android locked-in ecosystem, the former-search provider has broken its own record for the highest antitrust fine in EU history – last year’s $2.7 billion slap for manipulating search results.

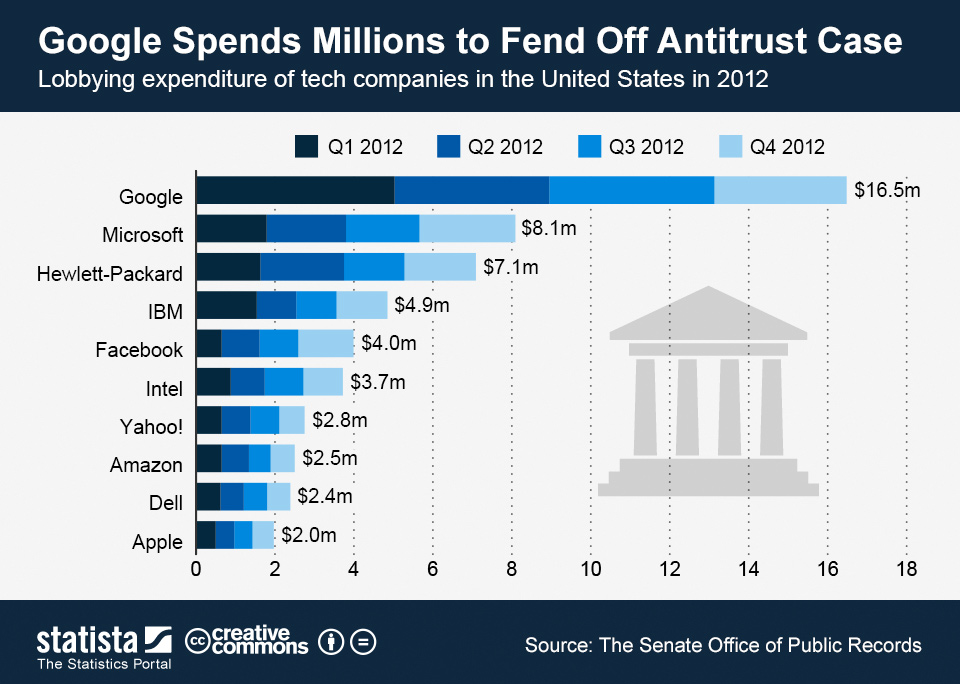

With so many lessons learned, and so much anti-US Tech sentiment in the EU (not all of it justified or even logical), we thought it might be interesting to look at just how Google got to a position where antitrust cases can be brought against pretty much any of their products. So much so, that in 2012 Google spent more than double that of second-placed Microsoft on lobbying in the US, with the specific goal of fending off antitrust cases before they even begin.

This figure reached $18 million in 2017, up from $16.5 million in 2012. Lovely stuff.

So, how did Google come to dominate the online world?

Search

Google is synonymous with search, with the verb itself now in common use. In fairness, they did improve on early attempts at functional search engines, particularly the back-end of the function – indexing, crawling, ranking etc.

No engine had come close to what Google were offering, and since it became popular in the late-90’s, its growth has been phenomenal. The 2000’s saw improvements in handling spam and manipulation, as well as the beginning of their acquisition phase. First up on the search front was Orion, an algorithm created by a student who went on to work for Google.

It would be four years before their next search-purchase, with 2010’s capture of Metaweb’s “Freebase” providing the first steps to an “open, shared database of the world’s knowledge”. Eventually, Freebase morphed into Wikidata.

In 2011, the capture of Apture signalled a shift, not just by Google but by the Web in general, to a more multimedia-rich experience.

Apture was created with the goal of transforming the internet…

from a flat “piece of paper” into a more powerful, interactive, intuitive and “hyper-relevant” multimedia experience.

This line of thinking would eventually spawn both good and bad experiences, ranging from useful mouse-over pop-up page previews on Wikipedia, to annoying text-link ads on “news” websites.

Next up for Google was to focus on language itself, with all its inherent contradictions and semantic labyrinths.

The $30 million purchase of Wavii in 2013, a natural language processing startup, added this ability to Google’s already significant resources. Apple were also interested in Wavii for their Siri endeavours, but the team ended up joining Google’s Knowledge Graph division instead.

By adding already-existing technology to their search product, Google ensured their dominance of search for years to come. It can’t be denied that, on this front, Google have been responsible for some of the most beneficial and game-changing advances of the internet era.

However, once results pages became infested with ads, and Google started inserting their own products ahead of competitors, the atmosphere was ripe for lawsuits. The $2.7 billion EU fine in 2017 was a direct result of such activity.

Ads

Google’s first acquisition in the advertising space was Applied Semantics in 2003, for a healthy $102 million. The name “AdSense” was a adopted by Google, having been coined by Applied Semantics.

By adding semantic text processing technology to its stack, Google unleashed their “fast-growing content-targeted advertising offering”. This was to become one of the most crucial aspects to the success of Google as an advertiser over the coming decade.

Co-founder Sergey Brin:

This acquisition will enable Google to create new technologies that make online advertising more useful to users, publishers, and advertisers alike.

It’s no surprise to see why Google felt Applied Semantics’ AdSense was a must have:

- AdSense technology processes the actual content of Web pages, whereas Google technology is only based on URL/Web log statistics.

- AdSense uses its CIRCA ontology to understand and extract key themes of a page, whereas Google relies solely upon user trends and patterns, which are often inconsistent.

- AdSense has the ability to discern ambiguous terms; Google has no disambiguation capability.

- AdSense provides advanced filtering technology; Google has no objectionable or competitive filtering mechanisms.

The next major acquisition came in early 2006 with the purchase of dMarc Broadcasting, also for $102 million. This was an attempt to integrate the AdWords platform to radio, by utilising dMarc’s automated radio ad insertion technology.

Although it seemed like a good idea at the time, this adventure was culled in 2009, citing these reasons:

- Hard to track radio ads

- Clients were too small

- Publishers were less willing to change

- Stations were “frustrated” with Google’s way

In 2007, Google made perhaps their most profitable acquisition to date by buying DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, calling it “the next step in Google advertising”.

This single purchase empowered Google to reach and serve advertisers, publishers and agencies, with the end goal of serving more targeted ads to its users.

Other notable additions include AdMob, Invite Media and Admeld.

AdMob was one of the first companies to serve ads inside mobile applications on the Android and iPhone platforms.

![]()

The purchase of AdMob in 2010, for a cool $750 million, signalled the first tentative steps into the profitable world of mobile advertising. Similar to DoubleClick, it gave Google an immediate window into the relationship between publisher, advertiser and agencies, but on mobile devices. It also prevented any competing companies from acquiring the technology, a common theme throughout this piece.

Invite Media is a Demand Side Platform, bought by Google for $81 million in June 2010. What is a DSP, though?

A DSP enables advertisers to buy advertising inventory (i.e. where their ads are shown) across a wide range of publishers via online exchanges, offering access to huge numbers of impressions globally through a single buying point.

Admeld joined the Google family in 2011. It’s an ad optimization platform for publishers, and cost $400 million. By allowing publishers to manage multiple ad networks and exchanges in one central location, its value was clear: a one-stop-shop is exactly what Google had been trying to become.

By acquiring companies who already perfected (or at least improved) the various stages of the advertising chain, Google now had the power to become the very thing antitrust was designed to prevent – a central provider for all things online ad-related.

Mobile

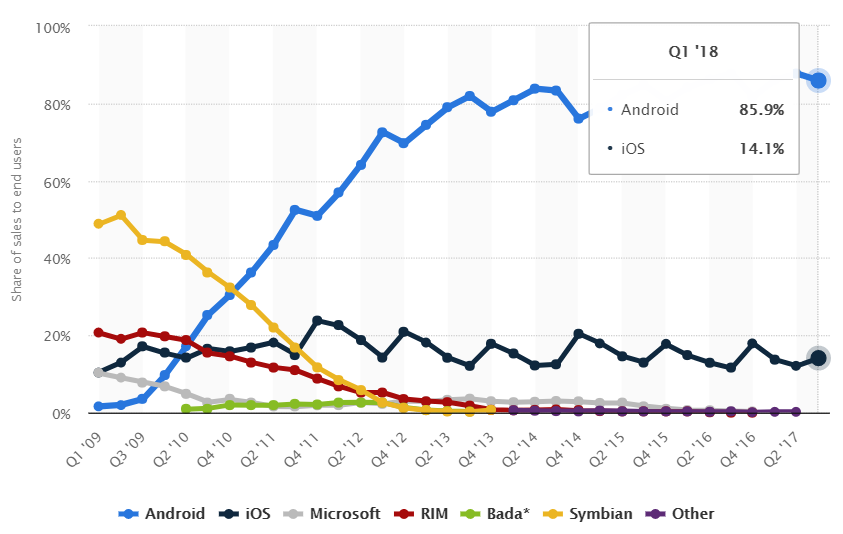

The world loves Android smartphones. In fact, almost 86% of all mobile sales in 2017, worldwide, were Android devices.

It all began in 2005 with the acquisition of Android Inc, a whole two years before the first iPhone was released. It was a strong signal of intent, and one of the most beneficial purchases Google have made.

In response to Apple’s ingenuity, Google announced the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) in November 2007 – they were scared silly that we all faced:

….a Draconian future, a future where one man, one company, one device, one carrier would be our only choice.

Irony aside, it was a noble thought at the time.

By launching their operating system as open source, essentially giving it away for free, Google had created a “Trojan horse” for their wider suite of services.

The scene was now set, and the following decade saw Google’s mobile offering improve, expand across the world, and increasingly lock developers and device manufacturers into their ecosystem, leading to the latest $5 billion antitrust case.

For a deeper history of how Google cornered the mobile market, Ars Technica have revived and refreshed a 2013 article on this very issue, titled Google’s iron grip on Android: Controlling open source by any means necessary.

It could have been different, and so much worse

Long before Google, Facebook or Manchester City became successful, Microsoft were the company everyone envied. With MS Windows enjoying well over 80% of the worldwide desktop OS share in 2018, they sat atop the pile for a very, very long time. Recent attempts to diversify haven’t been quite as successful, but there’s no denying their place in the history of technology.

Before Google went public in 2004, rumours circulated that Microsoft was planning a takeover, but ultimately Google didn’t bite. With hindsight, the thoughts of these two behemoths combining their strengths (and endless failings) is rather terrifying.

Had Microsoft’s proposed merger taken place, the internet may look a very different beast today. Imagine a walled-garden within your desktop, itself within another walled-garden, with the only relief being another walled-garden, but on your phone. And all tied back to the mothership in Redmond.

Interestingly enough, Google’s latest antitrust fine is a very similar situation to where MS found themselves in back in 1998. Replace “Android” with “MS-DOS”, “Chrome” with “Internet Explorer” and you’re on the right track.

Is Antitrust our friend?

It’s no mystery why most fines for antitrust are cases taken in the EU. Given the ability to pump millions into lobbying and the “friendly persuasion” of politicians in the US, the lack of interest in punishing these cash cows is perfectly logical, and somewhat depressing. Had Microsoft tried to buy Google all those years ago, antitrust should have prevented the deal going through – but with so many pivotal events and innovations happening after 2006/7, regulators may not have spotted the potential dangers.

Yet, here we have Google, a company full of ideas, genius and forward-thinking, failing to be forward-thinking enough to envision a situation where further acquisitions and mergers put them in the cross-hairs of regulators.

Sadly, it’s unlikely to make any difference. Firmly entrenched in the model of surveillance capitalism, and with even more potentially competition-limiting acquisitions taking place in 2018, notably pumping $22 million into KaiOS, it seems the fines are hugely outweighed by the profits.

Google made $109.65 billion profit in 2017. A fine of $5 billion is 4.56%.

Is that a deterrent? No – it’s an operating cost.

Leave a Reply