Significant steps are being taken by the AMP team to address the main criticisms that are repeatedly cast at the project. Plans are in place, or at least forming, to allow non-AMP technologies to enjoy the same search results page benefits as AMP pages.

Is it too good to be true? Let’s take a look at how we got here.

The AMP letter

AMP has been besieged with a steady stream of criticism since its launch. The main pain points for critics include:

- The co-opting of the URL

- AMP SEO bias in search results

(You can read more about these criticisms of AMP here). Since AMP’s launch, similar criticisms have resurfaced on a weekly basis. They reached a crescendo at the start of 2018 when they culminated in an open letter, published on January 9th, that has since been signed by over 600 individuals, and includes Daniel Applequist, and Ethan Marcotte amongst the original signatories. The goal of the letter: to register the signatories’ deep concern that AMP is reinforcing Google’s dominance of the Web.

The letter politely suggests two changes, which directly address the two criticism mentioned above:

Instead of granting premium placement in search results only to AMP, provide the same perks to all pages that meet an objective, neutral performance criterion such as Speed Index. Publishers can then use any technical solution of their choice.

Do not display third-party content within a Google page unless it is clear to the user that they are looking at a Google product.

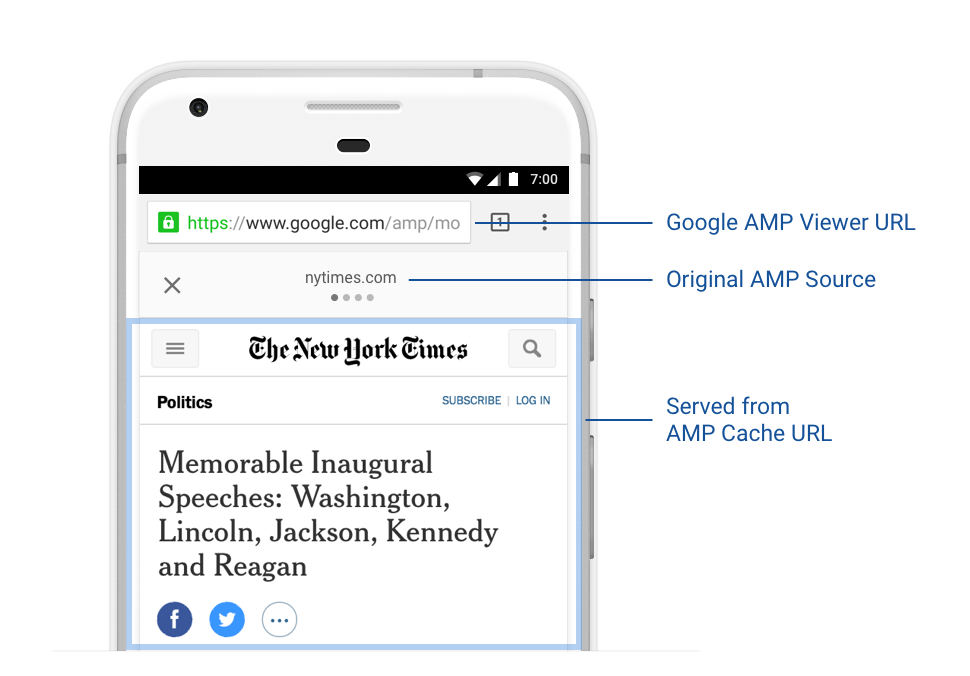

Improving URLs for AMP pages

On the very same day the AMP letter was published, the AMP project published a post entitled “Improving URLs for AMP pages“ about how they were working on changes to the controversial AMP URL:

We are making changes to how AMP works in platforms such as Google Search that will enable linked pages to appear under publishers’ URLs instead of the google.com/amp URL space while maintaining the performance and privacy benefits of AMP Cache serving.

AMP URLs (Source: amproject.org)

AMP URLs (Source: amproject.org)

Working with the W3C TAG group, the proposed solution was to be based on the emerging Web Packaging Standard. Crucially though, such a solution requires the emerging standard to be widely adopted and implemented in all major browsers:

Our goal is that Web Packaging becomes available in as many browsers as possible

Gaining respectability: AMP, standards, and the W3C

That the AMP team was working with W3C TAG (Technical Architecture Group) on the URL issue was a positive sign that they were serious about addressing its criticisms. The AMP team has always been open about the limitations of the approach, and frequently delivered robust explanations about why it needed to be built in the way that it was (having verifiably valid AMP pages meant that Google can guarantee the pre-loading performance magic indicated by the lightning badge), and that if it was technically possible they would display the original URL.

Working with the W3C to build open, technical solutions to these issues demonstrates, at the very least, good faith.

So what about the carousel and the AMP lightning badge search results page benefits that are only available to pages built with AMP?

Opening the AMP carousel up to non-AMP tech

The good news is that the improvements didn’t stop with the AMP URL. On March 8th 2018, a post by Malte Ubl, the AMP project lead, declared:

we now feel ready to take the next step and work to support more instant-loading content not based on AMP technology in areas of Google Search designed for this, like the Top Stories carousel.

Sounds promising! How would all of this be achieved?

For alternative non-AMP technologies to make it into the carousel, they will have to

- meet a set of performance and user experience criteria and

- implement a set of new web standards, some of which proposed standards include Feature Policy, Web Packaging, iframe promotion, Performance Timeline, and Paint Timing.

Google’s goal is to extend support in features like the Top Stories carousel to AMP-like content that (1) meets a set of performance and user experience criteria and (2) implements a set of new web standards. Some of the proposed standards in the critical path are Feature Policy, Web Packaging, iframe promotion, Performance Timeline, and Paint Timing

To summarise the approach, the post ends:

We are taking what we learned from AMP, and are working on web standards that will allow instant loading for non-AMP web content. We hope this work will also unlock AMP-like embeddability that powers Google Search features like the Top Stories carousel.

Too soon to celebrate?

This all sounds great: AMP is going down the open standards route with the W3C, the URLs will be fixed, and AMP sites won’t be treated more favorably than non-AMP sites. We just have to wait until the new set of proposed standards is in place, and implemented across all browsers. OK… So there’s a catch.

While the AMP team appears to be doing everything it can to allay its critics, the open standards approach is a double-edged sword. It’s certainly the right way to go, and probably the only approach that would be acceptable to its critics. However, by it’s very nature the process of defining and standardising web technology, any technology, is excruciatingly slow. (As an example, the HTML5 spec took 15 years to complete!)

This has led some critics to voice skepticism at the new announcements, even if they are well-intentioned. Ethan Marcotte cut straight to the nub of it:

Until such a point as those standards get finalized, and then they’re adopted by a significant number of browsers, AMP’s going to work exactly the way it has. To put a finer point on it, nothing about AMP is changing today, in the short-term, nor in the medium-term. In fact, it’s entirely possible that nothing will change at all. For the time being, web pages written in AMP—and hosted on Google-owned or -approved servers—are going to be the only thing allowed in the carousel.

On the one hand, it’s great that AMP is going down the standards route to address it’s core issues. On the other hand, this very approach presents a new problem in that it will be a painfully slow process and possibly years before the actual changes come to fruition. What will the web look like in a couple of years? Will AMP even exist then?

Perhaps another way to look at these developments, is to focus on the goals of AMP as a performance enhancing technology, rather than on AMP itself:

The AMP Project is an open-source initiative aiming to make the web better for all. The project enables the creation of websites and ads that are consistently fast, beautiful and high-performing across devices and distribution platforms.

In this case, then even if the proposed standards do take several years to come to mainstream, the web will still have gained much: new performance related standards that can be used to measure and predict performance, better ways to guarantee a good user experience, and better browser security for web apps.

AMP performance under scrutiny: is it as fast as you think?

Like any framework, it’s only fair to put it under scrutiny, especially where bold performance claims are made. And that’s what Tim Kadlec has done in his post How Fast Is Amp Really?.

One point that has been repeatedly made by AMP’s critics is that AMP is actually slower than a well-built web page. This is certainly a valid point: AMP relies on a JavaScript library to orchestrate the downloading and rendering of the page, and this adds an extra layer on top of the browser. Tim mentions this a couple of times in his article:

Once again, it’s worth noting that none of these optimizations requires that you use AMP. Every last one of these can be done by most major CDN providers. You could even automate all of these optimizations yourself by using a build process.

The AMP team never claimed that AMP is faster than all pages. In fact, back in 2016 when AMP was first launched, Malte Ubl, the project lead made this very point: a well-built page will be faster than an AMP page. But for the average site-owner/publisher who doesn’t have the time, resources, inclination or know-how to build faster pages, for these sites, then AMP will be faster. AMP will improve load times on average.

Still, the findings in this article are interesting: while there are indeed performance improvements under certain circumstances, AMP may not be performing as quickly as you’d expect. It’s also a good reminder about all the different ways that AMP can be served and how they can differ in page load speed.

Open standards, performance, and the end of AMP

As Malte points out in his post, the proposed standards that will fix AMP URLs and allow non-AMP web pages to share the benefits enjoyed by AMP pages, have uses beyond AMP. As such, they are something to be excited about. The web beyond AMP will benefit from these standards.

It’s possible these travails may actually work against AMP in the long run. By leveling the playing field, and in solving the current issues with AMP, bringing new enhanced performance and security features to browsers, may in fact render AMP unnecessary, or at least pitch it amongst many other competing technologies.

I’m reminded of a post about mobile web transcoders. Mobile transcoders exist because we live in an imperfect world, where mobile web clients aren’t always compatible, whether because of performance or other rendering issues, with the technologies on the web. Transcoders bridge this gap, converting on the fly a web page into something usable for a device.

In a similar way, AMP exists because of a performance problem. If and when performance is no longer an issue, then AMP won’t be needed and may well disappear. If AMP helps to bring about this outcome, then it will have served its purpose, even if it ultimately brings about its own demise.

Leave a Reply